Learn a Jazz Tune on Bass – CTA by Jimmy Heath with Bass TAB – Bass Practice Diary – 13 April 2021

If you follow my Bass Practice Diary videos regularly you already know that I love to play jazz tunes on bass guitar. A few weeks ago I featured the tune for Freedom Jazz Dance. In that video I was playing a 6-string bass, but I want to show that you can do this on any bass, you don’t necessarily need 6-strings or 24 frets. This week I’m demonstrating the Jimmy Heath tune CTA on a Fender Precision with 20 frets.

CTA by Jimmy Heath

I first came across this tune on Chick Corea’s album Paint the World. It’s a jazz fusion album. The band on the album was called the Elektric Band II. The rhythm section was completely different to the original Elektric Band. It featured Gary Novak on drums, Mike Miller on guitar and Jimmy Earl on bass. However, it’s a really good album. I think it ranks up alongside anything that the more famous lineup of Dave Weckl, Frank Gambale and John Patitucci recorded. In fact I saw the classic lineup of the Elektric Band play two of the tunes from this album, CTA and Blue Miles when I saw them at the Barbican in London in 2004.

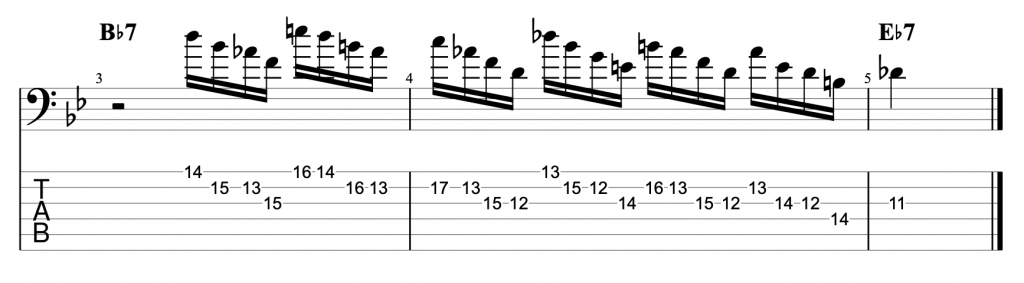

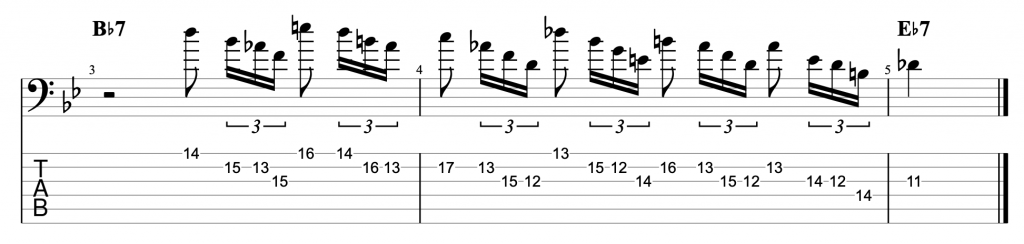

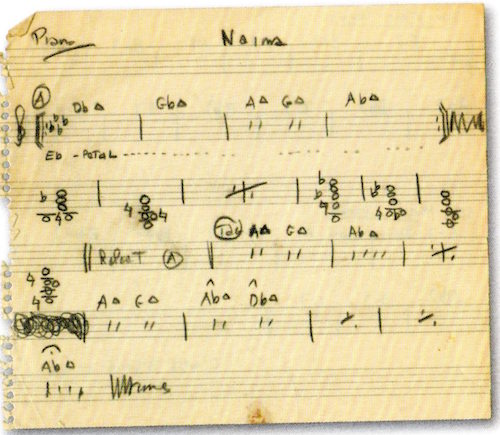

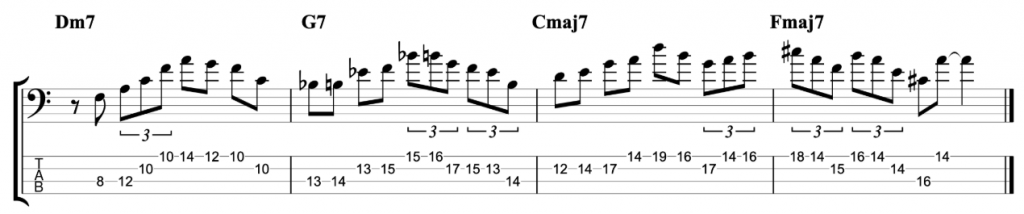

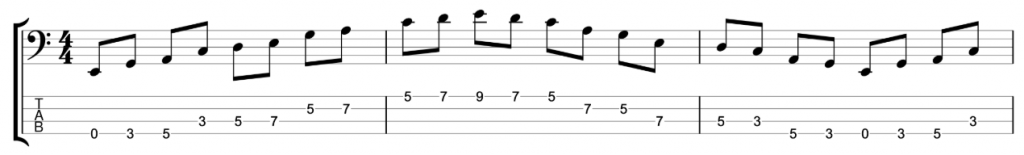

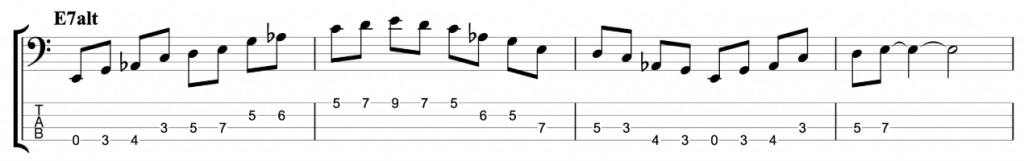

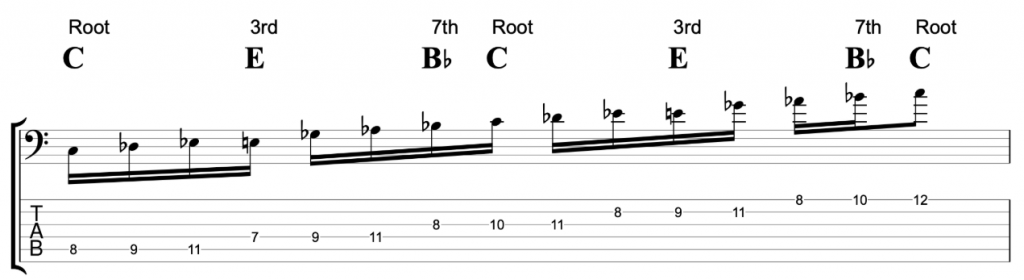

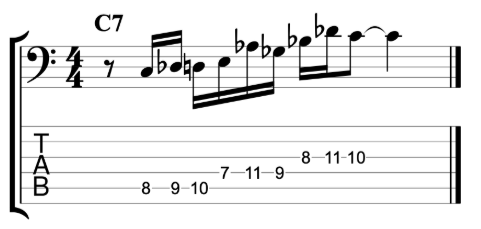

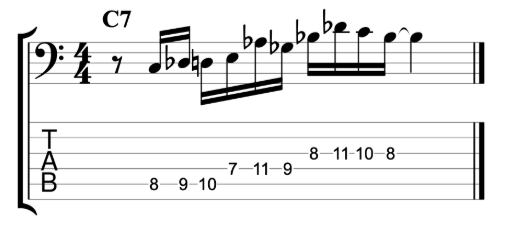

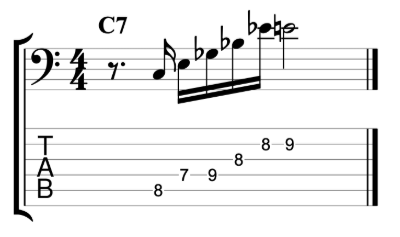

The Chick Corea version of CTA is very different from the original Jimmy Heath version. Jimmy Heath plays it in a bop style and he plays it with swung 1/8th notes. This is the opening melody from Jimmy Heath’s version.

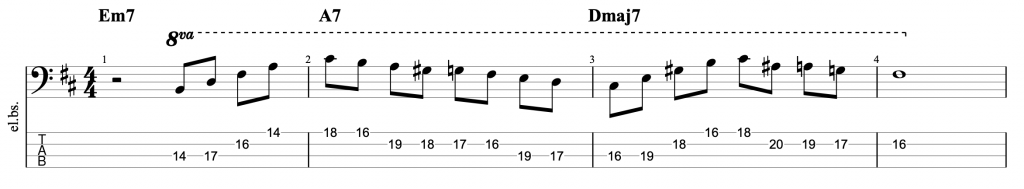

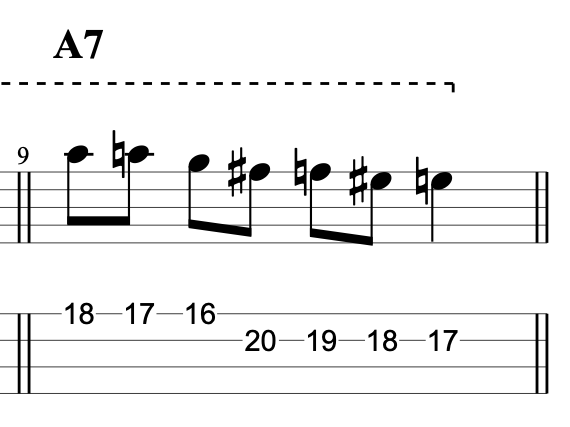

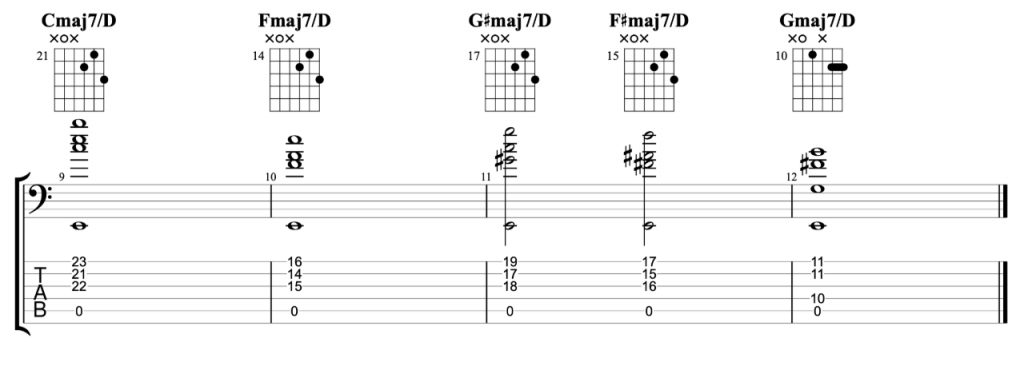

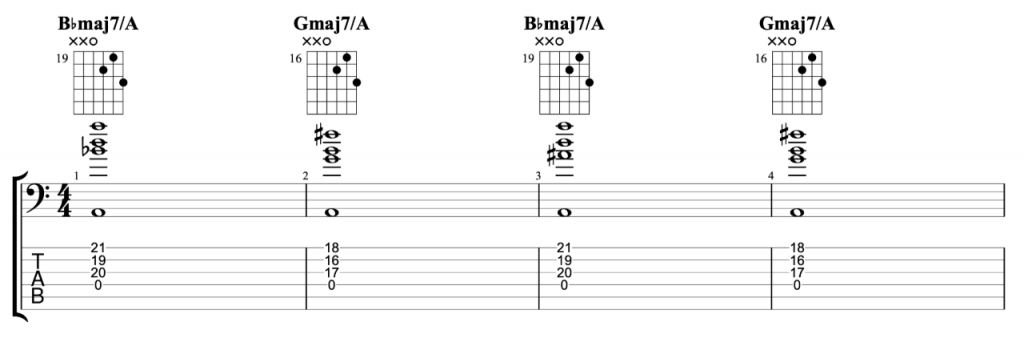

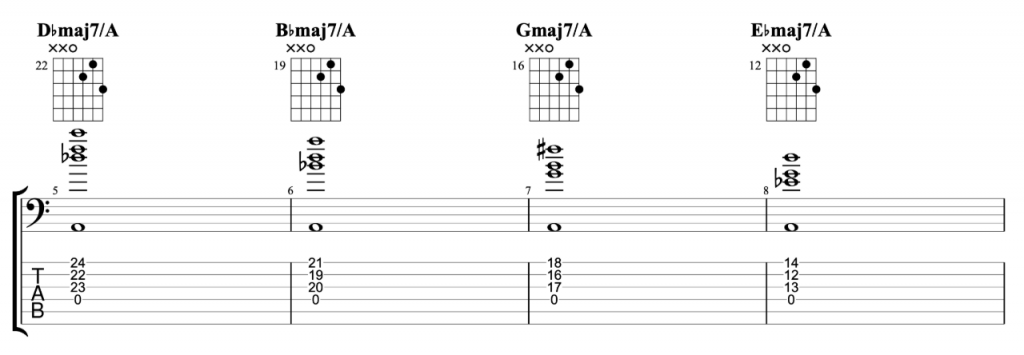

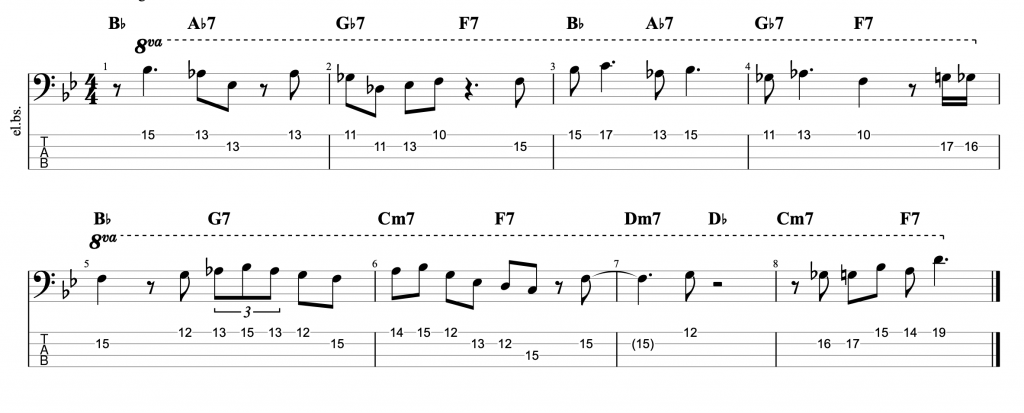

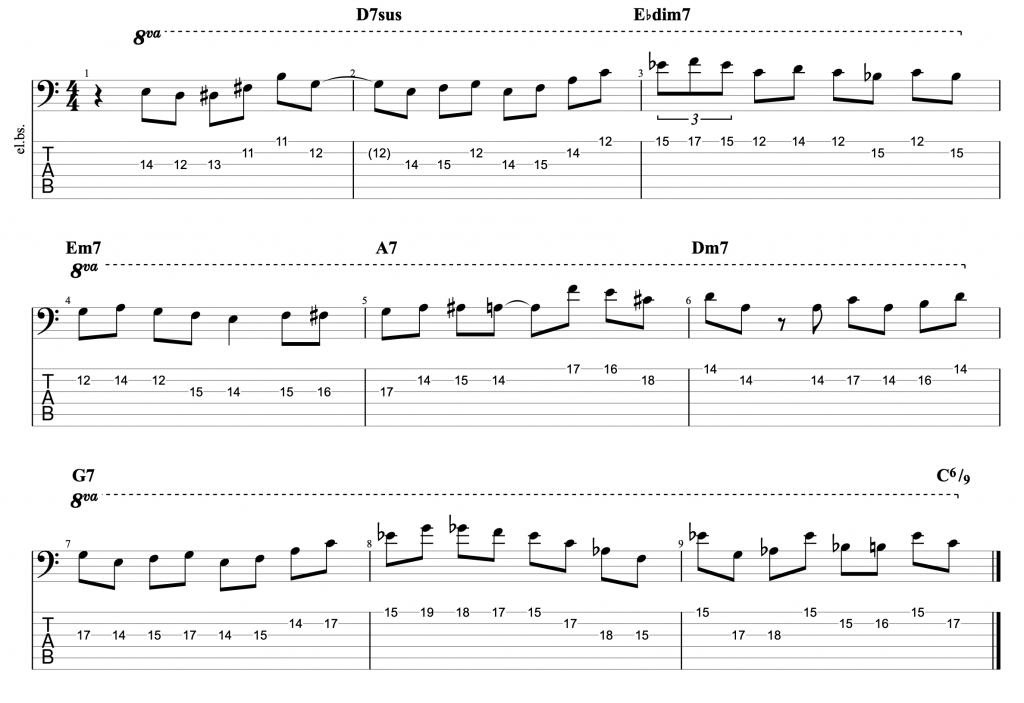

Chick Corea gives the tune a straight funky fusion feel. And there is a long section at the end which is added. It’s like a tag on the end of the melody. The key has also been changed from Bb to C. Here is the tag tabbed for 6-string bass.

How do you learn jazz improvisation?

I honestly believe that learning jazz melodies is fundamental to learning how to improvise. It’s even more fundamental than transcribing solos. A good jazz improviser will use the melody in a solo. So, if you work out a solo without knowing the melody, then you’ve missed the most important piece of the puzzle.

I wanted to feature a melody played on a Fender Precision. Because when I started doing this, I was working jazz melodies out on a P style bass with 20 frets and 4-strings. I think a lot of bass players think that jazz melodies and improvisation is only for a certain type of bass player that plays extended range instruments, but that does not have to be the case.

The first jazz melody I ever learned on bass was Goodbye Pork Pie Hat by Charles Mingus. It was famously covered by Jeff Beck and Joni Mitchell. But I didn’t know that when I was 15 years old. I knew Mingus’ version from the album Ah Um and then I heard Marcus Miller play it on fretless bass. I remember playing the melody on my red Vester bass as a teenager.

After learning that melody, I then started learning plenty more jazz melodies on my 4-string bass. My first bop style tune was Tricotism by Oscar Pettiford/Ray Brown. And I remember learning the Charlie Parker tunes, Confirmation, Donna Lee & Anthropology on 4-string before I made the switch to 6-string at 19 years old. I still remember most of the fingerlings that I worked out for those tunes on 4-string.

If you’re interested in taking this idea further, there is a book called Charlie Parker for Bass. It features melodies and solos transcribed and tabbed for 4-string bass. It hadn’t been published when I was learning this stuff, but I know some of my students use it now. When I was learning these tunes I was learning them from a Real Book (treble clef version).