Cascading Arpeggio Jazz Lick on 6-String Bass – Bass Practice Diary – 23rd February 2021

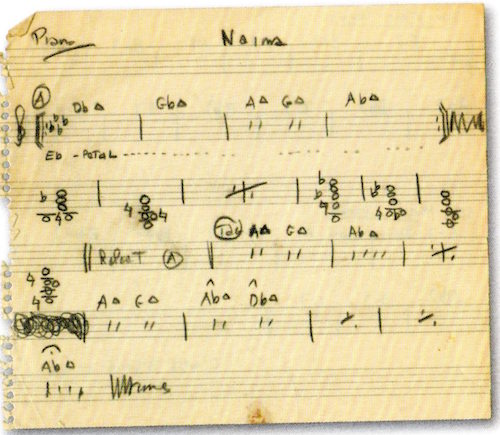

I recently introduced the concept of playing cascading arpeggios on bass with a video featuring some exercises. I mentioned in that video that this is a very versatile idea that gets used in a wide variety of different musical contexts. So, the obvious next step is to demonstrate a situation where I might use this idea. This video features a cascading arpeggio jazz lick which I’ve created to played on a jazz blues in Bb.

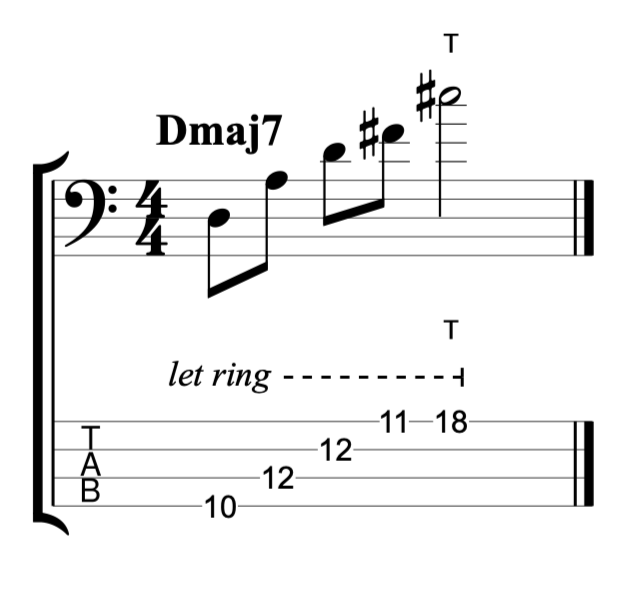

The Lick

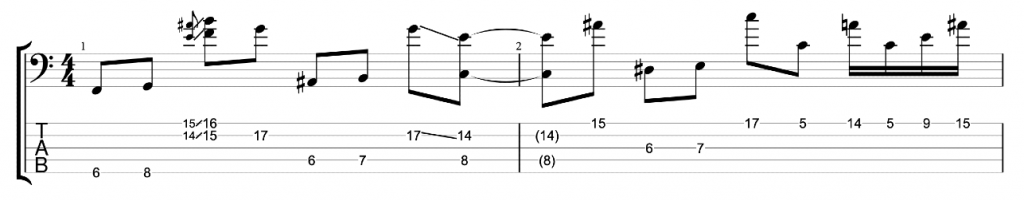

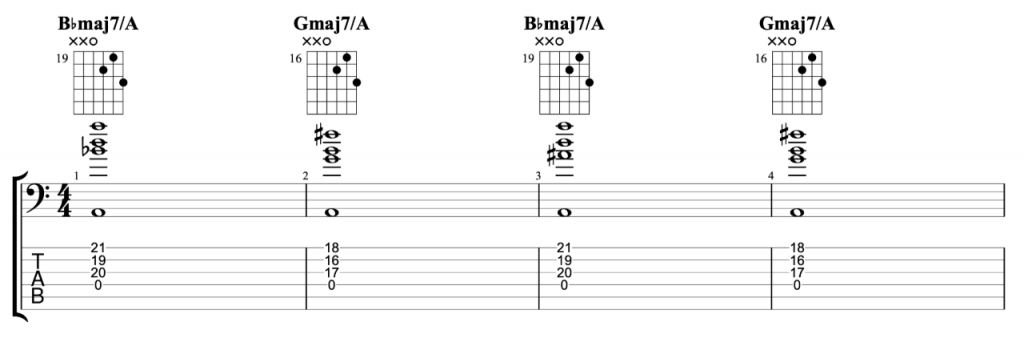

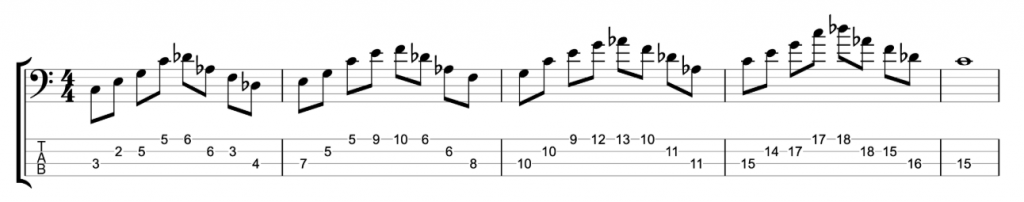

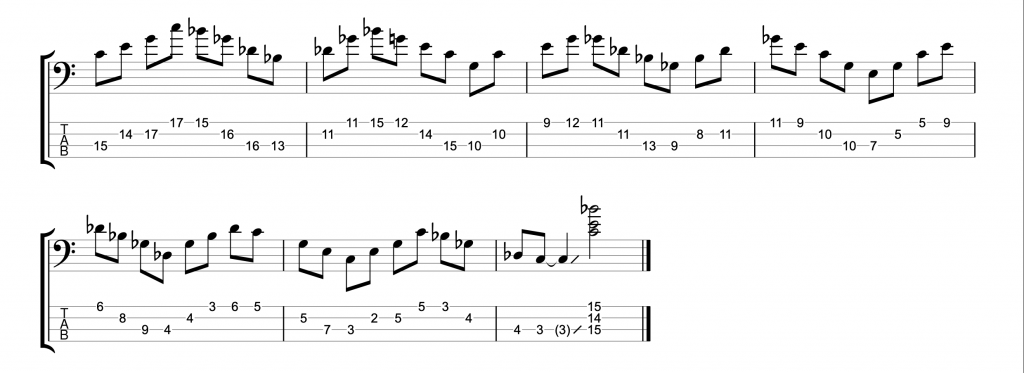

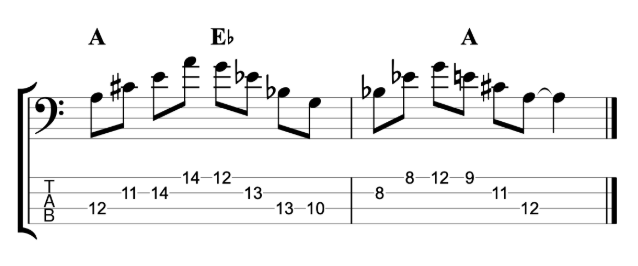

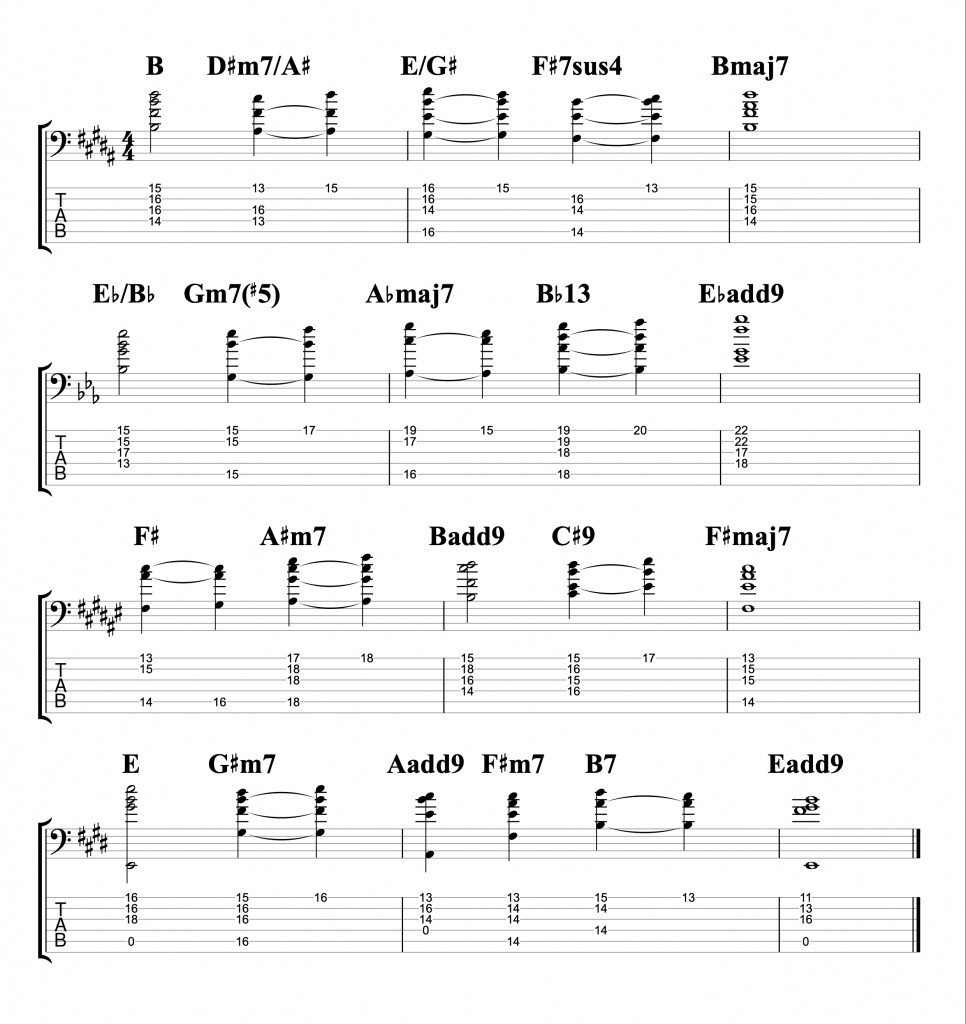

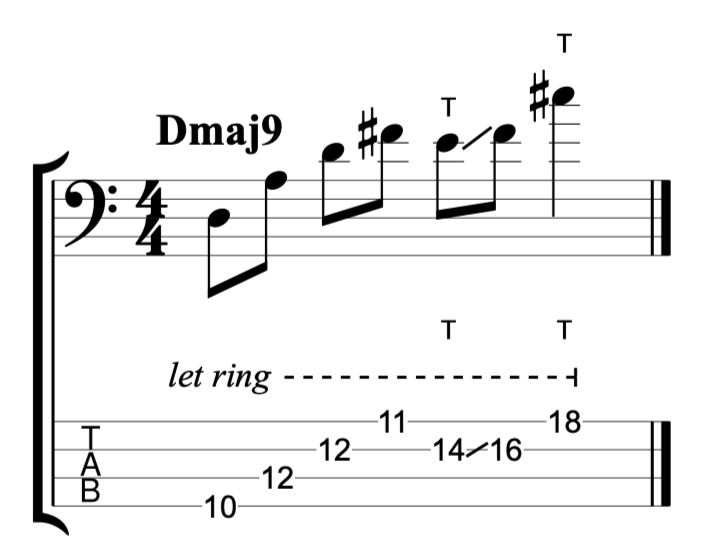

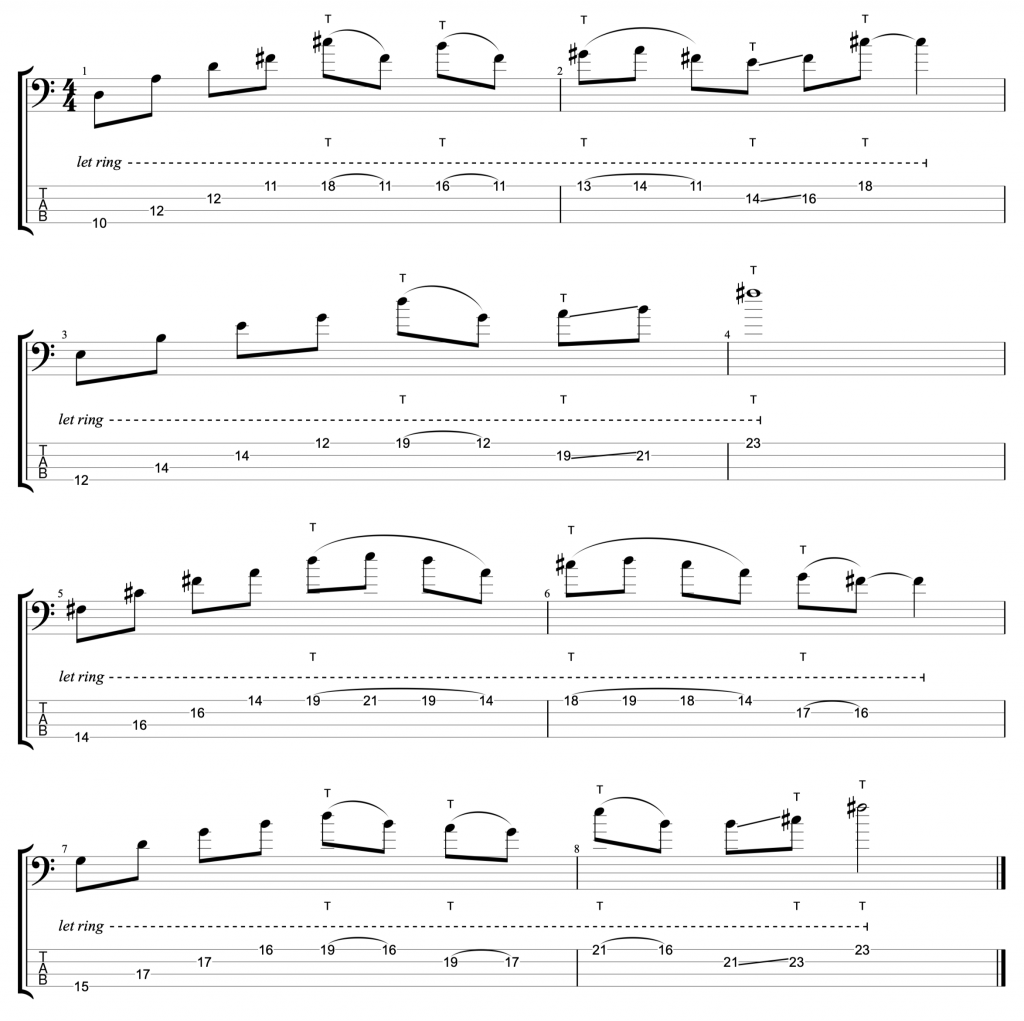

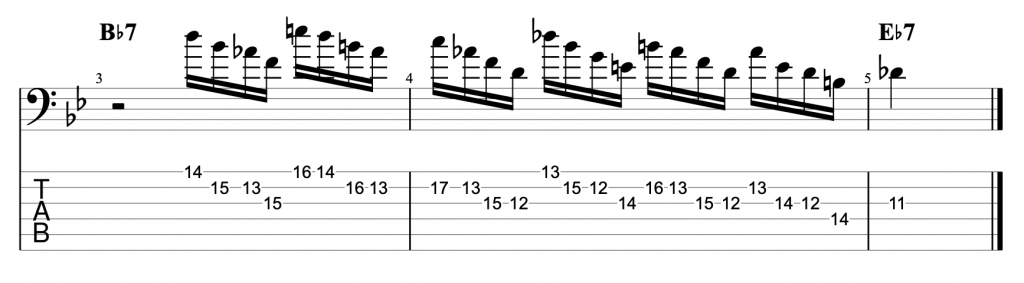

Here is the Cascading Arpeggio Jazz Lick.

The lick starts on the third beat of the third bar. It’s important to start in the right place if you want the line to resolve onto the Eb7 chord on beat one of bar five. I’ve written the line in straight 16th notes, which creates a polyrhythmic effect against a triplet swing feel. I’ve done a video about this in the past.

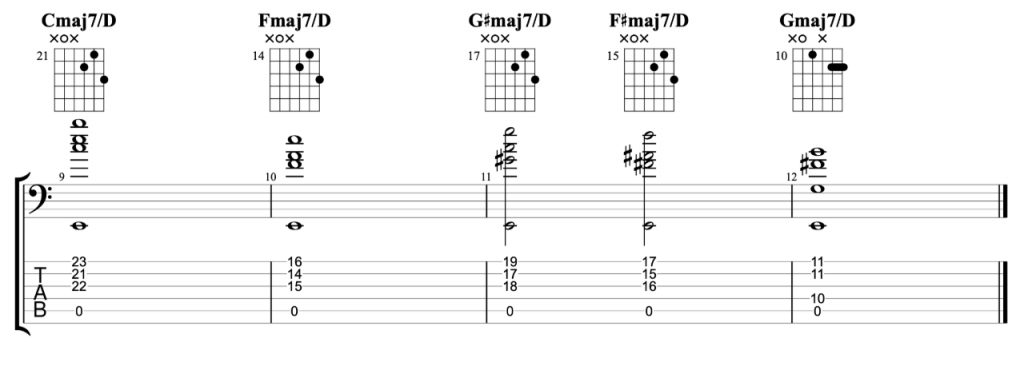

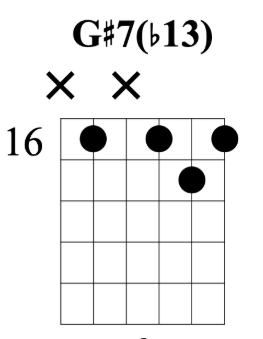

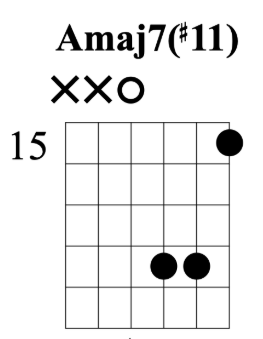

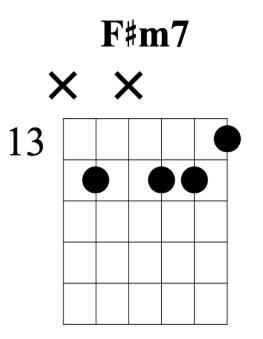

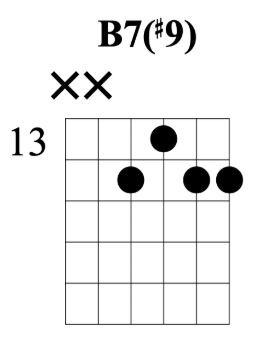

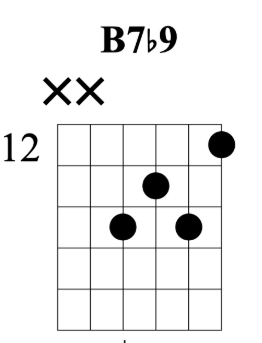

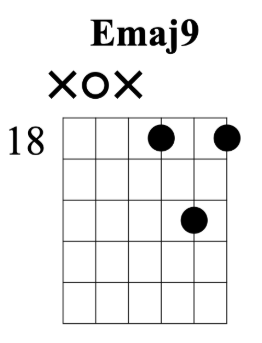

The first arpeggio in the lick is Bb7, starting on the third, D and coming down 3rd, root, 7th, 5th. Then I play an E7 arpeggio descending from the root note, E. E7 is the tritone substitute for Bb7. This is a common chord substitution in jazz. It works because the E7 chord shares two notes in common with the Bb7. The 3rd and the 7th, in this case D and Ab (G#). The third arpeggio which starts on beat one of bar four is a Dm7b5 or D half diminished arpeggio. However, this arpeggio is really functioning as a Bb9 chord.

The Diminished Arpeggios

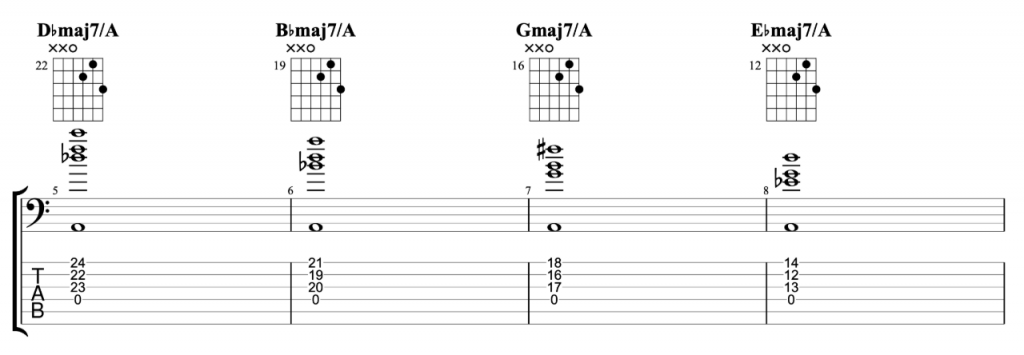

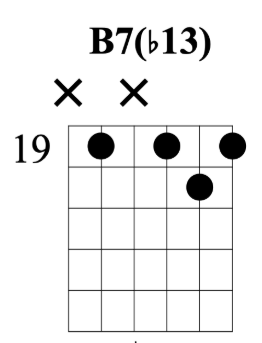

Then follows two diminished 7th arpeggios, Eo7 and Do7. I edited the explanation of these out of the video because it was a bit too long and boring, but I’ll include it here for those who are interested. Diminished sounds, both scales and arpeggios, work really well on dominant 7th chords.

You can think of a D diminished 7th chord as being a Bb7b9 chord without the root note. You can also play a Bb half/whole diminished scale over a Bb7 chord. I’ve also done a video about this sound. The scale gives you an interesting mix of inside and outside notes, Root, b9, #9, 3rd, #11, 5th, 13th & 7th. You can divide this scale into two diminished 7th arpeggios. Do7 gives you 3rd, 5th, 7th & b9, the other arpeggio gives you root, #9, #11 & 13th. In the video I’ve called this arpeggio Eo7 although you could also think of it as Bbo7, Dbo7 or Go7. I’m only thinking of it as Eo7 because in the inversion that I’ve used, the lowest note is the E.

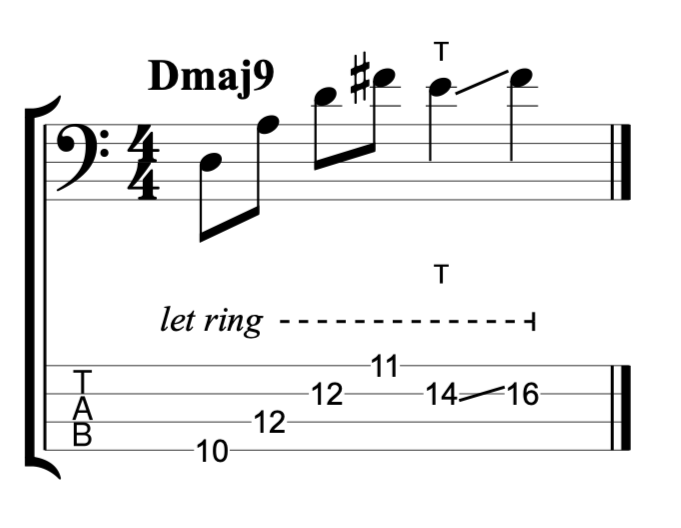

A rhythmic variation

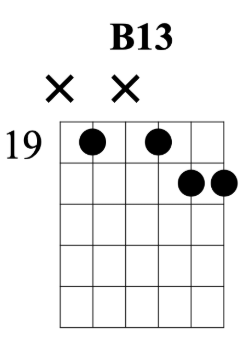

The final arpeggio is the tritone substitute, E7 again. This time descending from the third, G# (Ab). It’s very common to play the tritone sub on beat four of bar four of a jazz blues because it drops chromatically onto the four chord, Eb7, at the beginning of bar five. My lick resolves onto the note Db which is the 7th of the Eb7 chord.

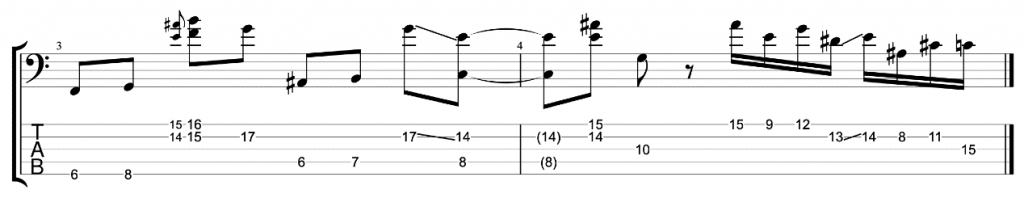

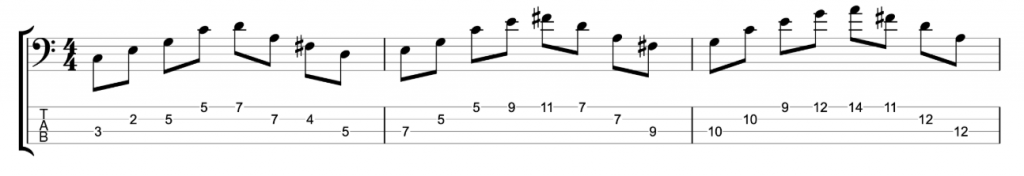

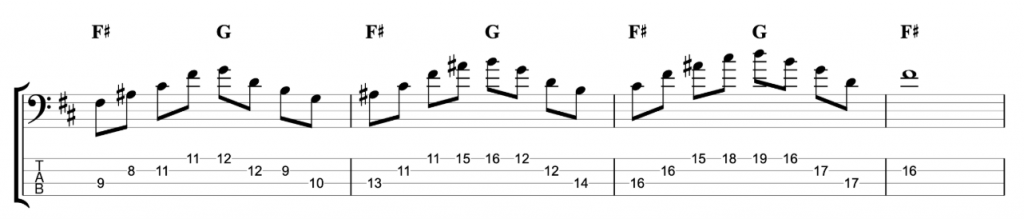

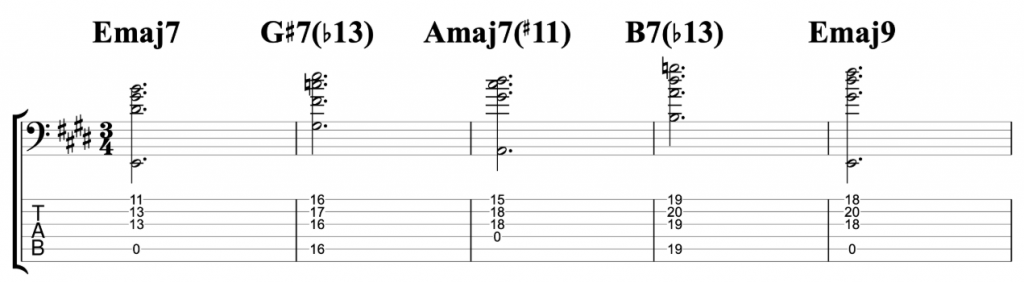

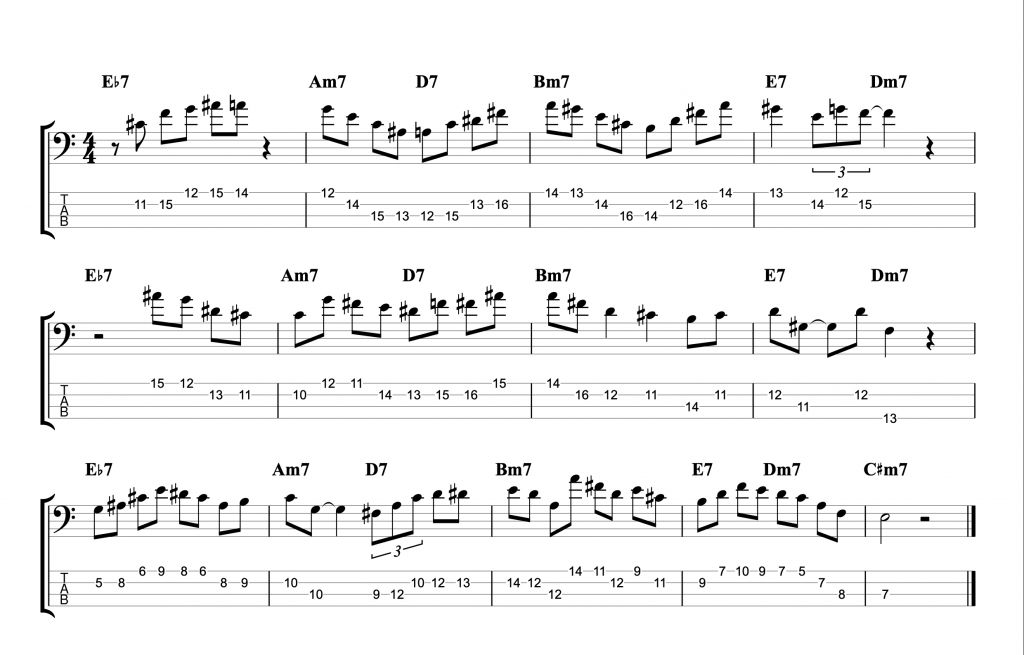

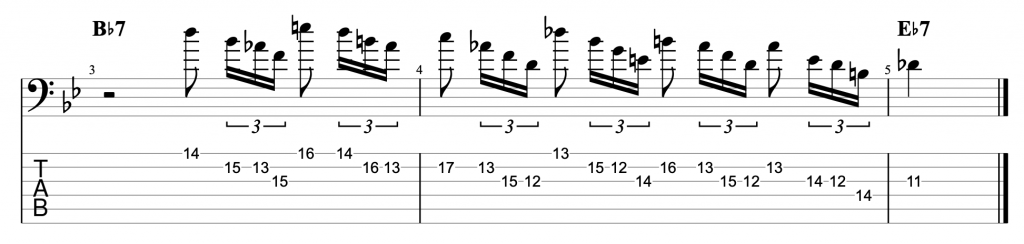

I’ve also included a rhythmic variation in the video, which is fun to play but difficult to execute even at relatively moderate tempos. It goes like this.

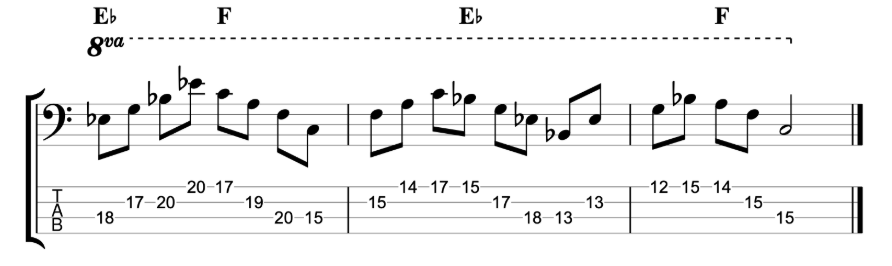

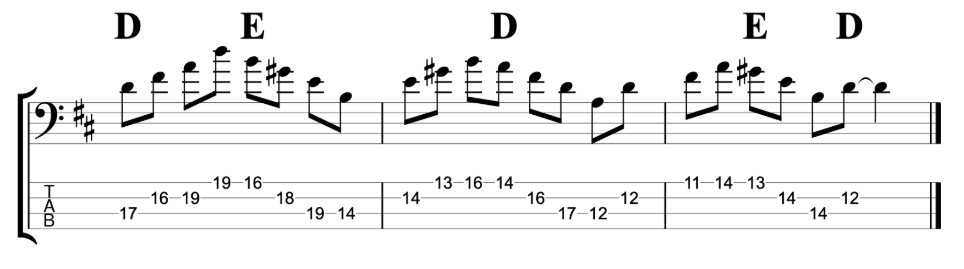

I finished the video by improvising three choruses of a blues in Bb, and inserting the lick in the appropriate place each time. My plan had been to improvise three choruses and pick my favourite chorus and only include that one. But I’m increasingly becoming less interested in editing myself as time passes. All of the choruses are ok while being flawed in some way (thank God! Nothing bores me like perfect music). And if people don’t want to watch all three choruses they are free to stop watching whenever they want. So I included the whole thing.

I had intended to play the variation on one of the choruses to see if I could execute it. But as you can see, that didn’t happen. I clearly need to practice more!