I VI II V Chord Progressions on 6-string Bass – Part 2 – Bass Practice Diary – 17th December 2019

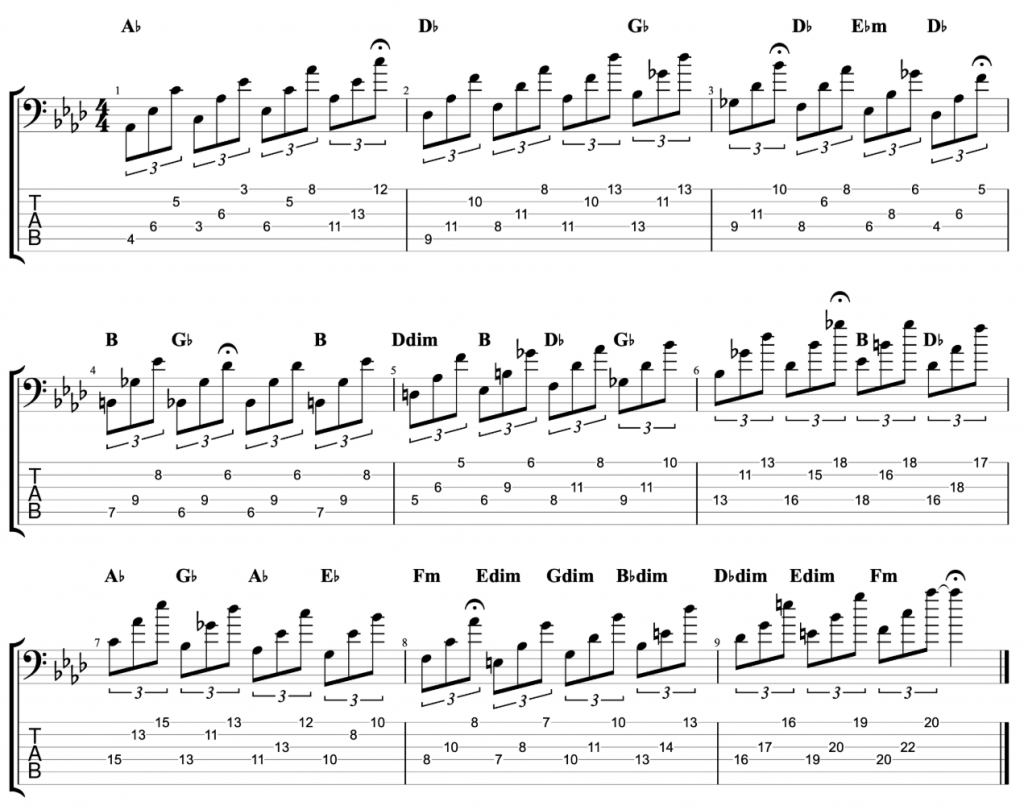

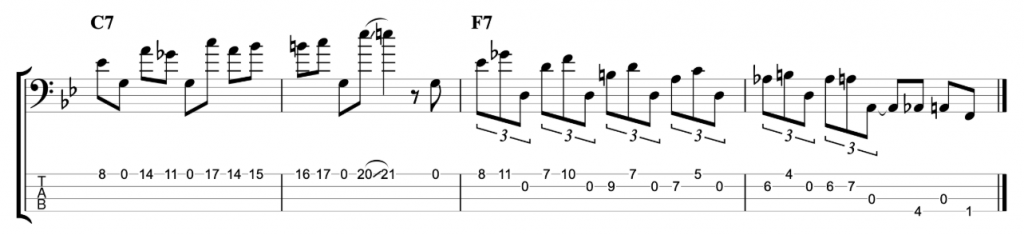

This week I’m revisiting my introduction to I VI II V chord progressions on 6-string bass video. There are so many ways that you can alter and substitute chords in a I VI II V sequence. Jazz musicians will often alter and add to the progression so much, that it’s almost impossible to tell that it was ever a I-VI-II V progression in the first place.

Chord substitutions

There really aren’t any rules when it comes to substituting chords. There are certain standard substitutions that are very common, such as the tritone substitution, which I looked at in my last video. But, honestly, you can substitute any chord for any other one that you like the sound of. A lot of it depends on the musical context that you’re playing the substitution in, but also it comes down to opinion. What sounds interesting to some people, will sound odd to others.

This week I’m just going to take you through some familiar chord substitutions and additions to I VI II V’s. These examples go quite a bit further than the examples in my previous video. But, believe me, you can take these ideas much further out than this.

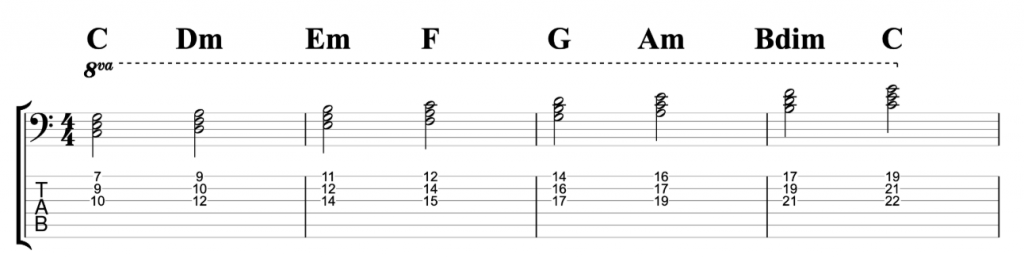

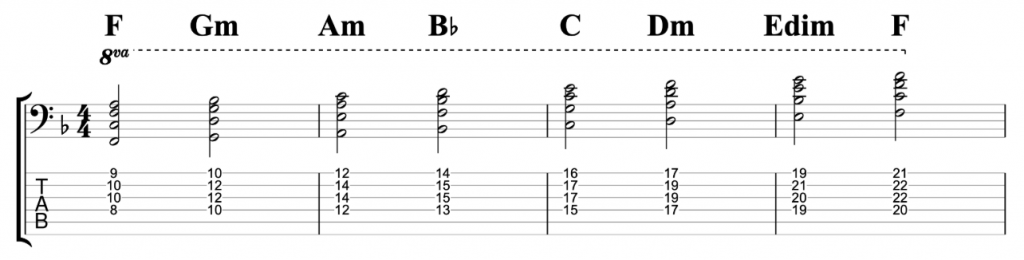

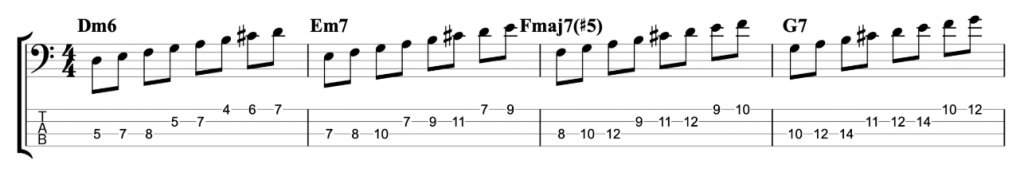

The I VI II V examples

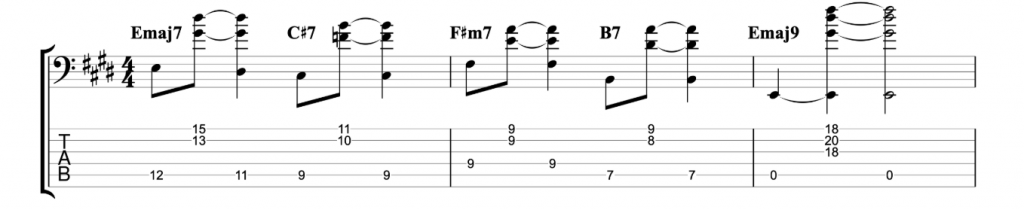

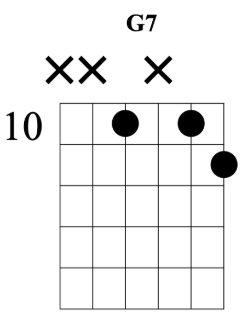

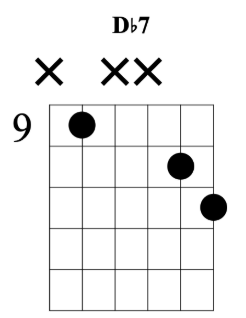

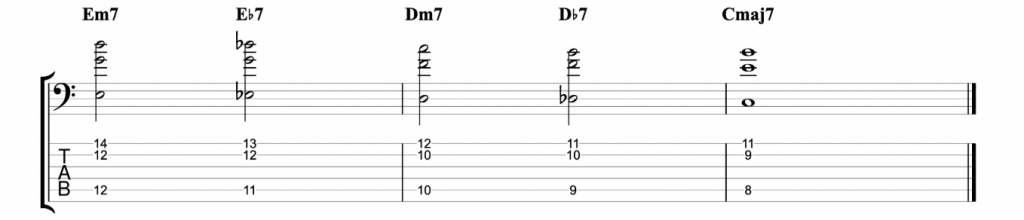

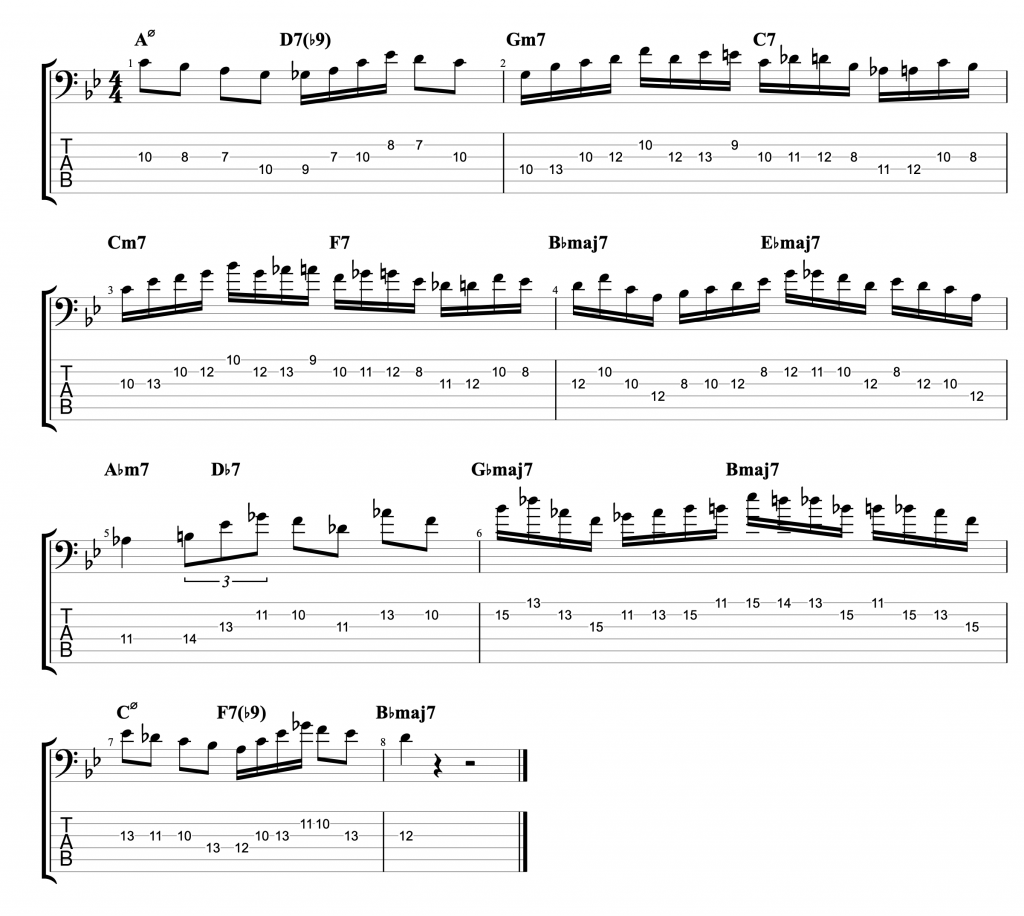

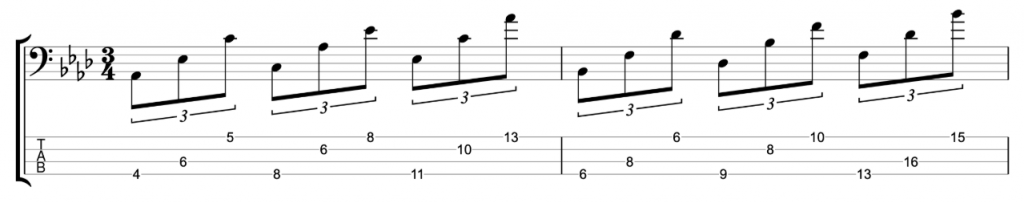

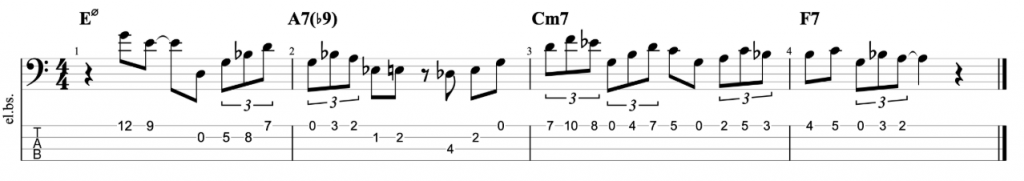

I created this first example by taking the III-VI-II-V example from my previous video and turning all the chords into dominant 7th chords. I then applied tritone substitutions to the VI and II chords. Then I added whatever extensions and alterations that I liked the sound of.

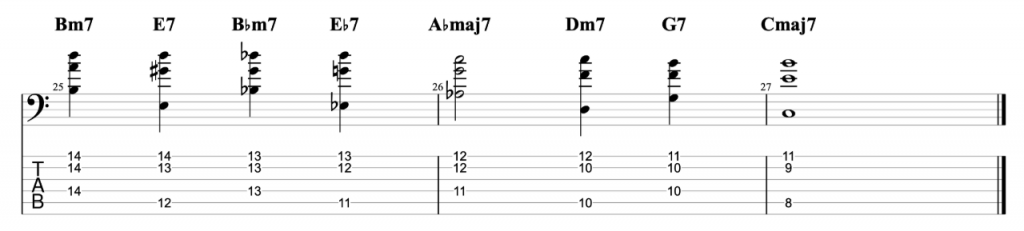

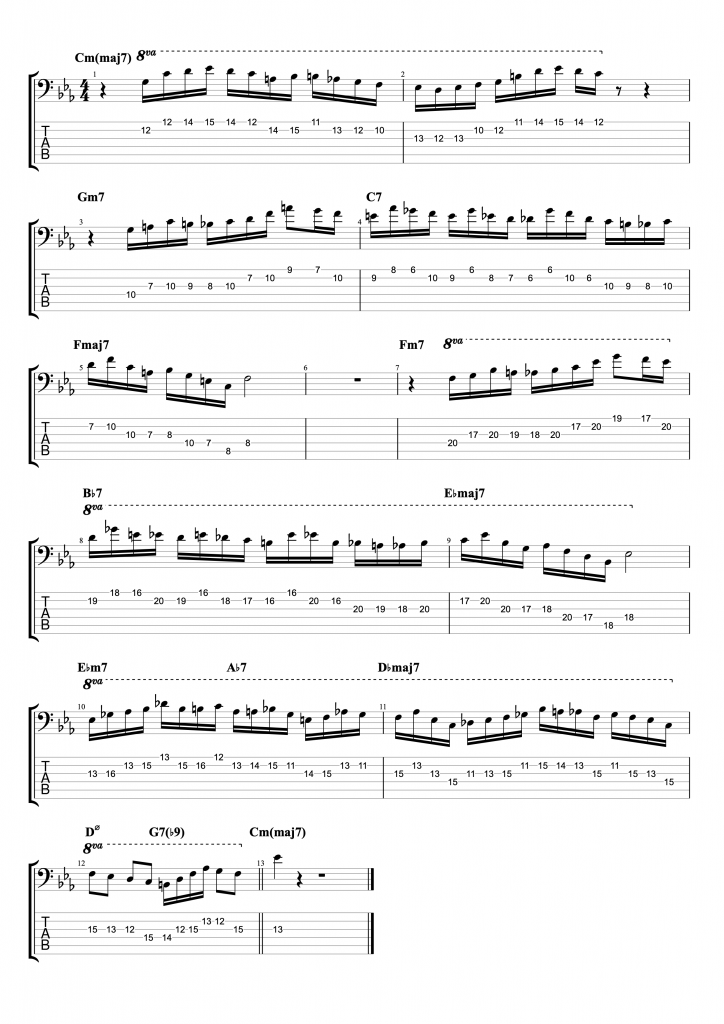

Once you have four dominant 7th chords like this, you can come up with so many variations just by applying tritone substitutions.

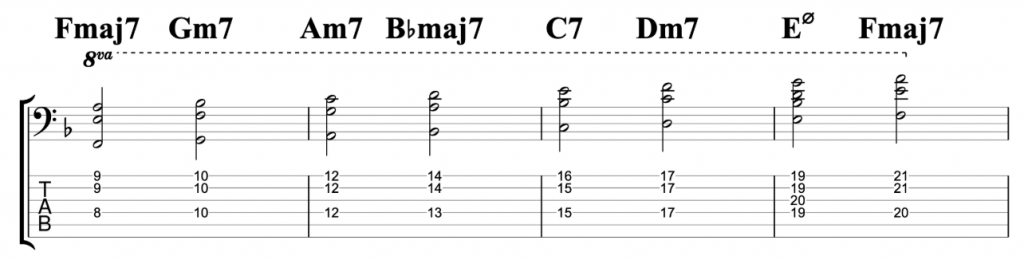

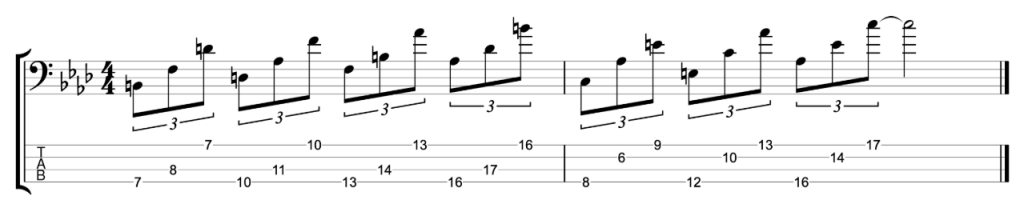

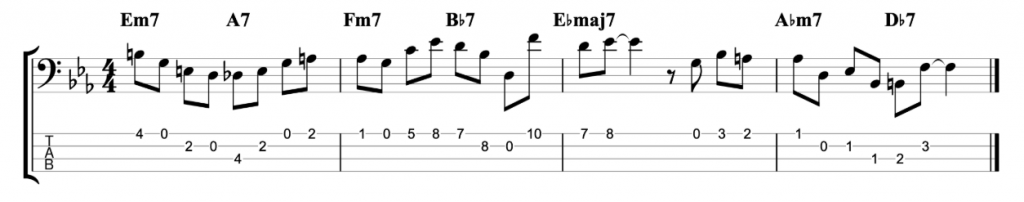

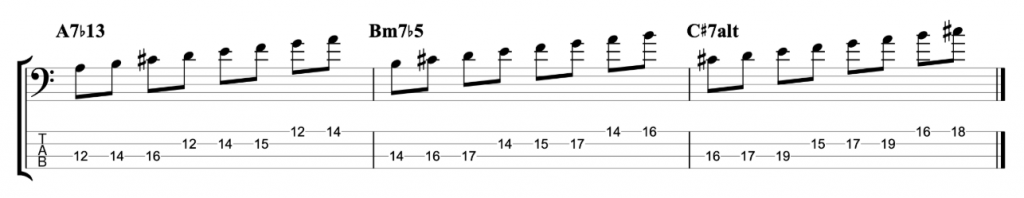

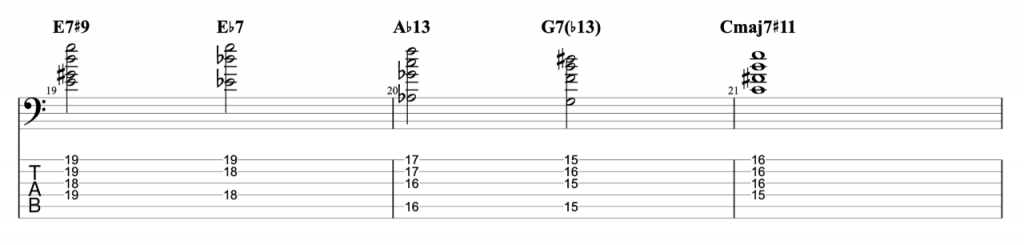

My next example derives from the first example. I’ve simply turned the E7, Eb7 and G7 chords into II-V’s. Meaning that I’ve added minor 7th chords before each dominant 7th chord. Each minor 7th has a root note that is a 4th below (or a fifth above) the root note of the dominant 7th chord. I’ve altered the VI chord to make it a major 7th instead of a dominant 7th chord. This completes a II-V-I in the key of Ab major, which is a strange thing to find in a chord progression in C major, but it works!