Can a Cheap Bass Sound Great by Adding a Good Pickup (Fender Custom ’62 P Bass Pickup)? – Bass Practice Diary – 21st April 2020

Can you get a good P Bass tone out of a cheap bass with the addition of a good pickup? This week I’m doing something a bit different. I’m bringing a bass back to life that hasn’t worked for somewhere in the region of 15-20 years. I’m literally changing all of the electronics, including the pickup, jack input and volume and tone pots as well as all the wiring. But the star of this is the Fender Custom Shop Custom ’62 Precision Bass pickup.

Vester Stage Series P Bass Copy

The bass in question is the first bass I ever owned. It’s a Korean made P Bass copy called a Vester Stage Series. My parents bought it for me in 1994 and it cost £150 when it was brand new. It’s actually quite a good copy of a Fender Precision. So good in fact that they were successfully sued by Fender in the 90’s and as a result, these basses didn’t last long.

There’s a lot on this bass that feels cheap. The original pickups are uninspiring sounding. The body is plywood, the scratchplate is cheap and flimsy and all the screws have gone rusty. But the main reason I say that it’s a good copy, is because the neck is really good. It’s very playable and it’s really in good shape for a cheap 26 year old bass. Other elements on the bass which are good are the tuners and the bridge. So there is the shell of a good bass, especially when you consider that the pickups, scratchplate and screws are all easy to replace. Would a solid wood body lead to a better tone than the plywood body? Probably a bit, but I personally don’t think that it would make a massive difference.

The Transformation

As I’ve already mentioned, the neck, bridge and tuners are in remarkably good shape for a cheap bass of this age, but the frets needed attention. So the first job, having removed the old strings was to clean the frets. A great trick for doing this is using 0000 grade wire wool. I would strongly recommend using electrical tape to protect the fretboard. You can get tools that go over the frets to protect the board, I have the tools but I don’t find that they work better than tape. In fact, I’ve found I can be more accurate with tape.

After cleaning the frets with wire wool, I polished them with Frine Fret Polishing Kit and I cleaned the fretboard with a normal guitar polish. I would normally use lemon oil but I wouldn’t recommend using lemon oil on a maple fingerboard.

Next I had to remove the scratchplate and the bridge. The bridge had to come off so I could remove the earth wire that runs through the body of the bass and attaches to the tone control pot. Having done that, the old input and volume and tone control pots were easy to remove. The old pickups were not easy to remove. The heads of the screws holding the old pickups in place were so rusted that no screw driver could turn them. It was very difficult getting the pickups out, I eventually had to break the old pickups to get the out of the bass and then get the screws out with pliers.

Installing the Fender Custom ’62 P Bass Pickup

By contrast, installing the new Fender Custom ’62 P Bass pickup couldn’t have been easier. I lined up the position by placing the old scratchplate in place. I made four new holes for the screws and then I fixed the pickup in place and soldered the two wires according to the instructions that came with the Fender Custom ’62 pickup. You really don’t need to be an electrician or even a DIY expert to do this. P style basses are really very simple to wire up.

If you want to do a similar transformation to your own P bass, you don’t need to change the pots or the input as I did. I changed mine because lots of the wires were rusty, which was why the bass didn’t work. And it’s cheap and easy to buy ready wired input, volume and tone setups from guitar shops. The only fiddley job is connecting the earth wire from the bridge to the tone control pot.

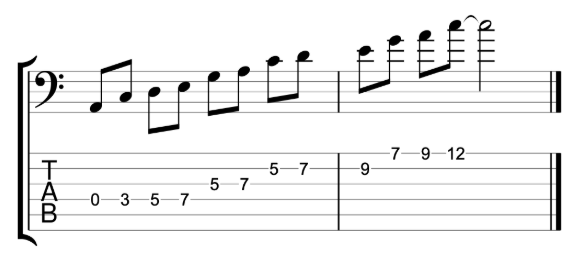

To complete the installation of the pickup, I would strongly recommend setting the pickup height individually for each string. This is to ensure that you get an even sound across each string. I set my pickup heights by measuring with a metal ruler and then adjusting the heights by either tightening or loosening the four screws. The measurements I was aiming for were E – 3.9mm, A – 3.8mm, D – 3.7mm and G – 3.6mm. Although I wasn’t trying to be too specific, I don’t think my measurements were perfectly accurate. Those measurements were just a guide to get the heights roughly right, and the rest is done by playing and listening.

How to Set up a Bass

If you’d like to learn the basics of setting up a bass, then check out this video.