Blues in A with a 10/8 Time Signature – Bass Practice Diary – 24th September 2019

Blues is at the root of so much of what I play. I started out by playing blues as a child. And the blues is also at the root of so much modern music, including jazz, rock, funk, soul… the list goes on. It’s actually incredible when you think about it, how the musical vocabulary of the blues has permeated so much music in the last 100 years or more. But, can you play a blues in an odd meter? That’s what I found myself wondering this week.

Where does blues end and modern jazz start?

Blues has its own rhythmic feels and distinctive harmony. Which have proved very adaptable to other genres of music. And it could be argued that once you break out of these structures, you’re no longer playing the blues. My own musical journey through my teen years took me from blues to modern jazz, simply by a process of trying to expand my harmonic language. It wasn’t a conscious decision on my part to leave the blues behind. I simply started to become interested in upper chord structures and alterations, and expanding my role as a bass player, and modern jazz is where I found myself.

So I’ve no doubt that some people could argue that an odd meter blues isn’t blues, it’s (blues influenced) modern jazz. But I would argue that if you can stay true to the rhythmic feeling, structure and harmony of the blues, while playing an odd meter. Then you can play an odd meter blues. And that’s what I’ve tried to do in this video.

The influence of John McLaughlin

It’s not a completely original idea, although I’ve never heard anyone try to do exactly what I’ve done here. However, I was partly inspired by the jazz guitarist John McLaughlin. There’s a tune called New Blues, Old Bruise on his album Industrial Zen. It’s in 15/8 and I think it’s a brilliantly original approach to playing blues harmonic language. That tune would undoubtedly be classed by most people as jazz fusion, but nevertheless, the blues influence is undoubtedly present.

The other influence of John McLaughlin came from his brilliant DVD called Gateway to Rhythm. In which, he briefly demonstrates a kind of subverted blues shuffle feel in 10/8. The rhythmic phrase he uses is Ta-Ki-Ta Ta-Ki-Ta Ta-Ka Ta-Ka, which is 3+3+2+2. When I heard it I thought it was genius. Because it seemed to capture the feel of a blues shuffle, but it wasn’t a shuffle. I think the phrase originally came from one of his old Mahavishnu Orchestra albums.

Hearing that made me think, if you can capture the feeling of a shuffle in 10/8 then maybe you can play an entire 12 bar blues in 10/8. I haven’t used that particular rhythmic phrase in my blues, because I didn’t want to copy John McLaughlin’s rhythmic phrase. But it did inspire me to come up with the blues in 10/8.

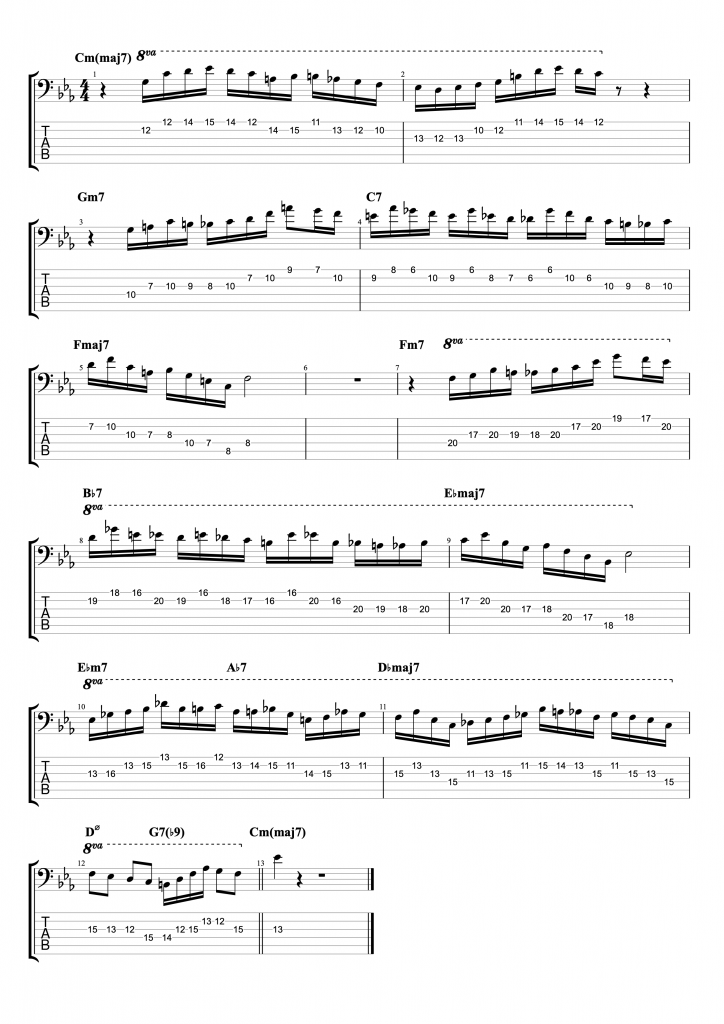

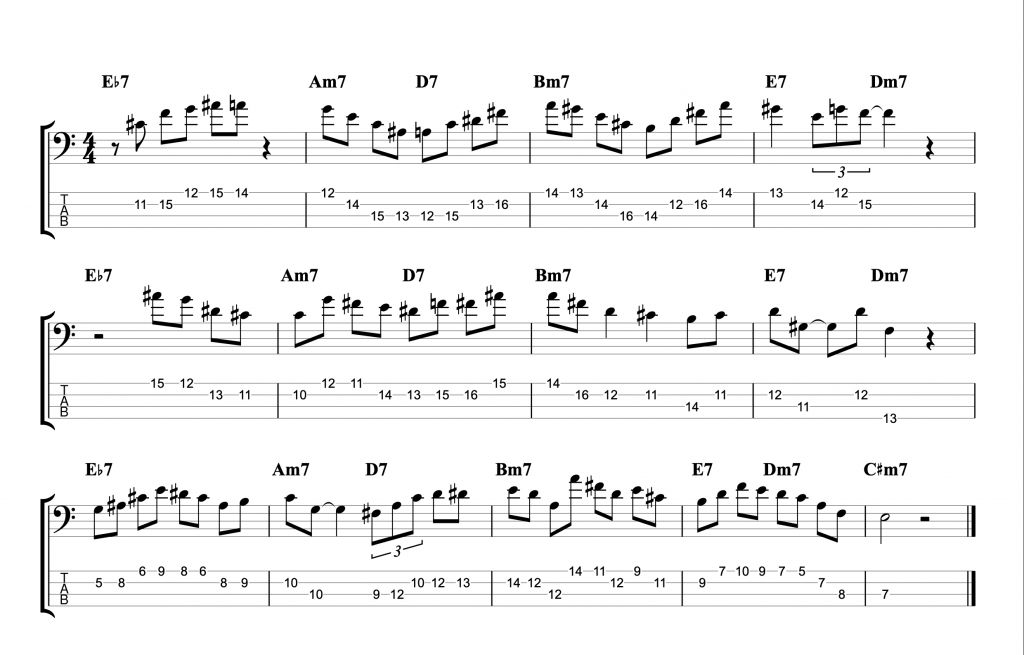

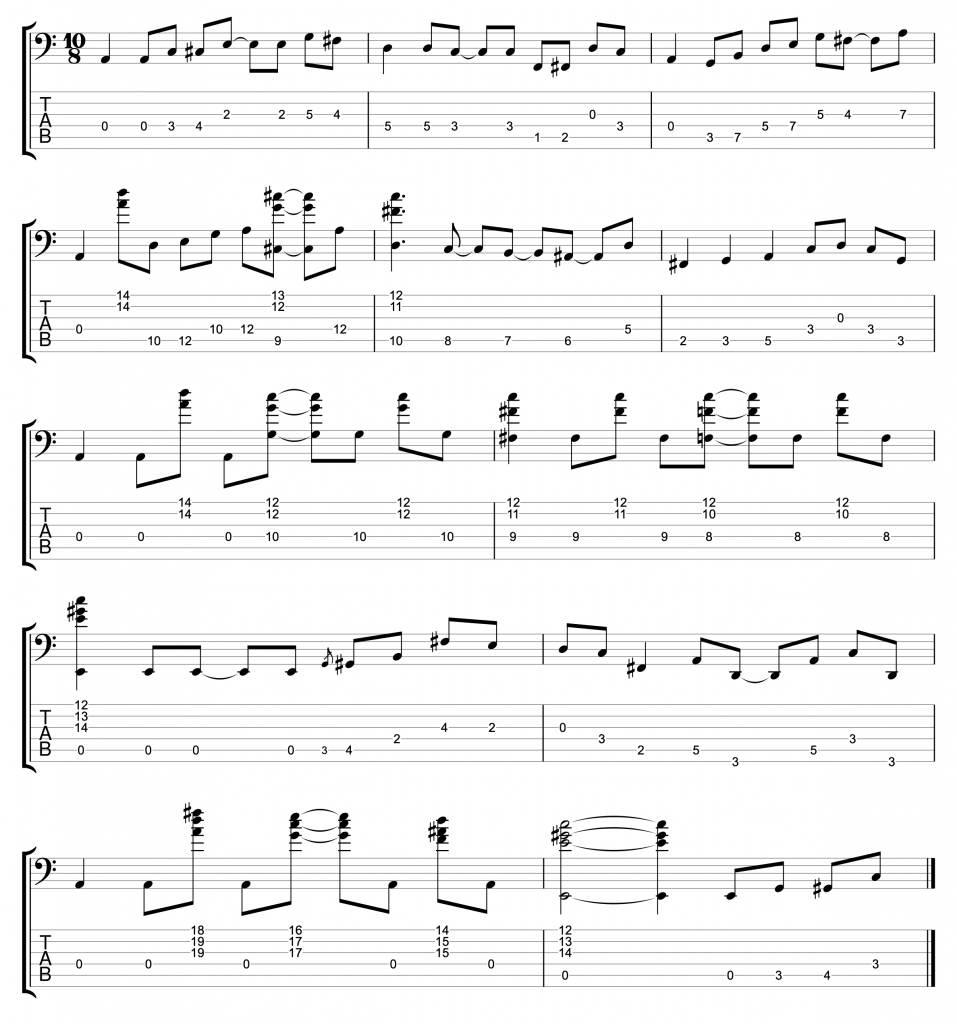

The bass line

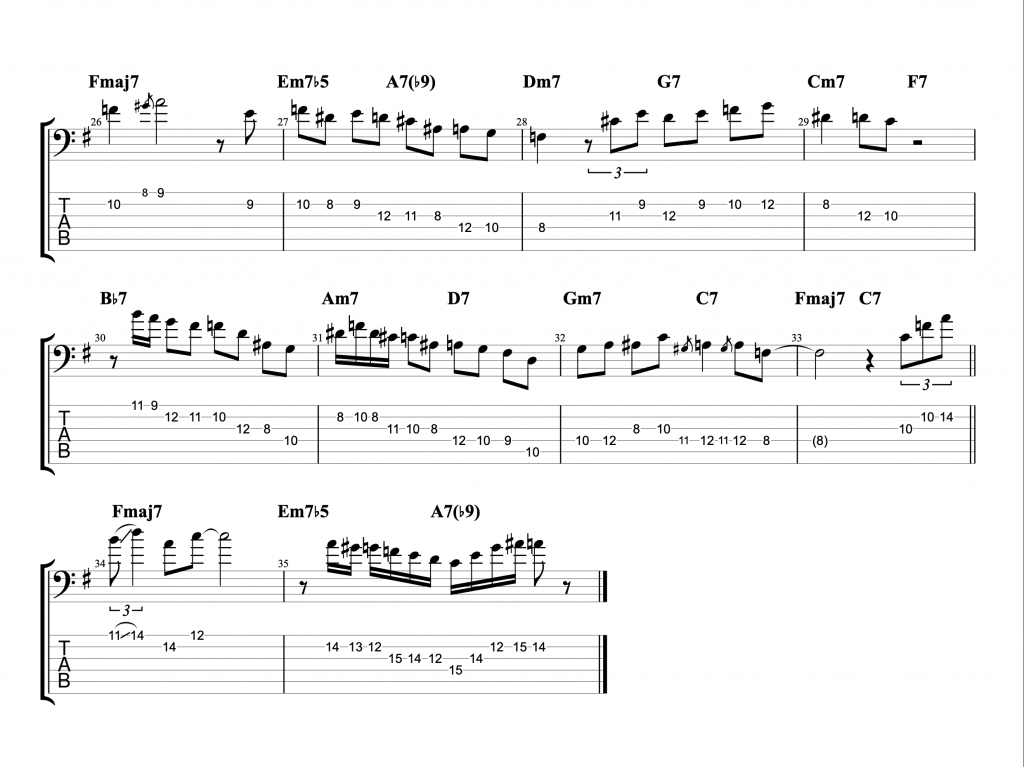

The bass line was partly improvised and partly worked out in advance. It turns out that you have to concentrate really hard when you’re playing a 12 bar blues in 10/8. Especially when you don’t just stick to one rhythmic phrase. As I haven’t here, I’ve tried to mix up the rhythms as much as I could. But here is one chorus of transcribed blues bass line in 10/8.

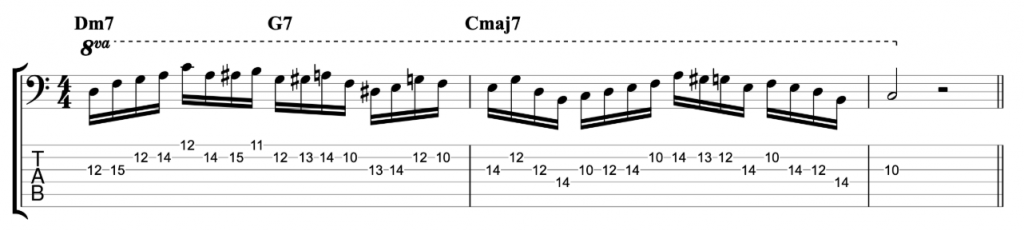

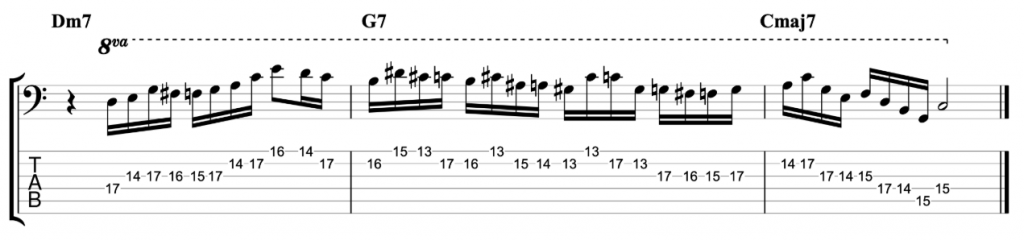

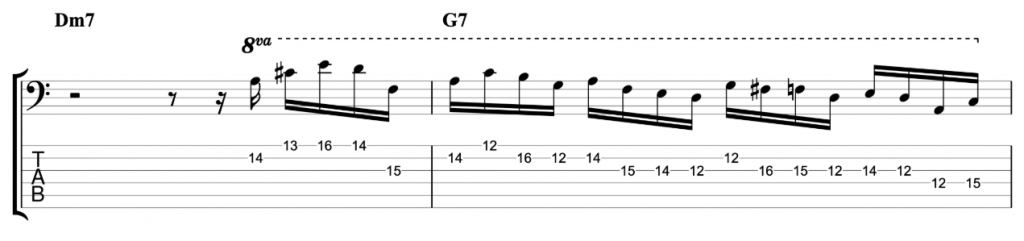

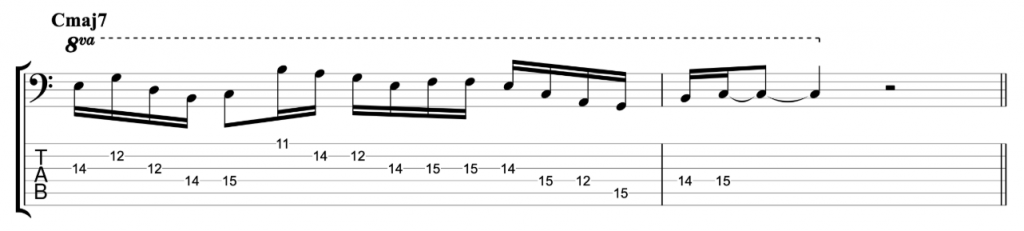

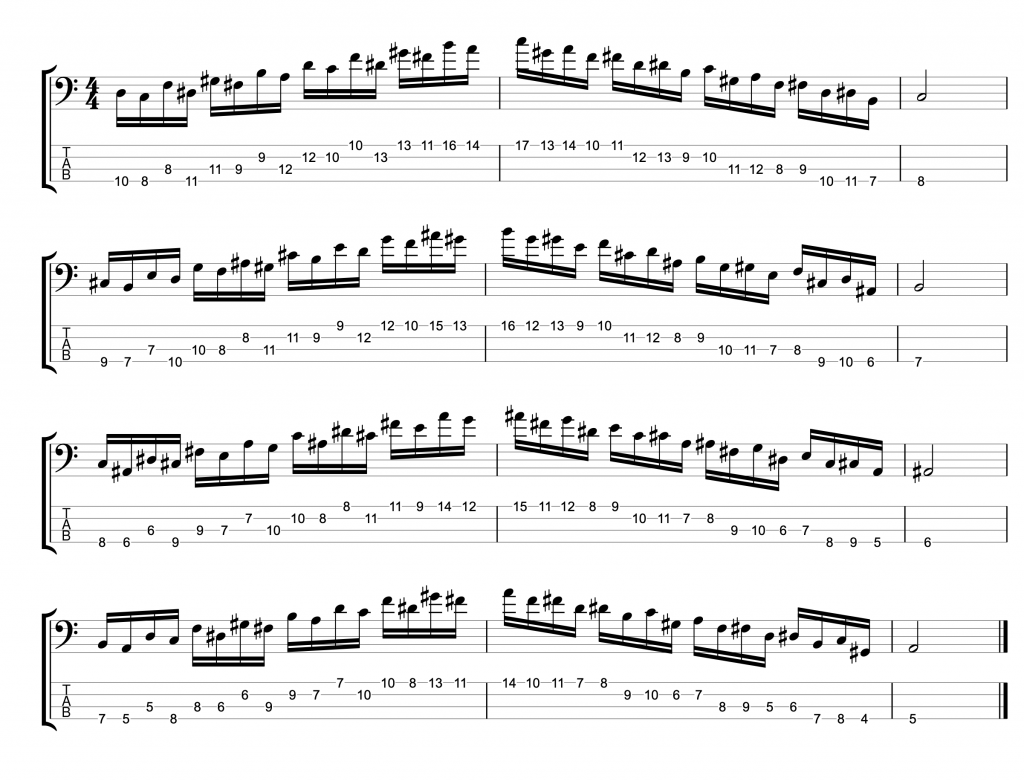

The fretless bass solo

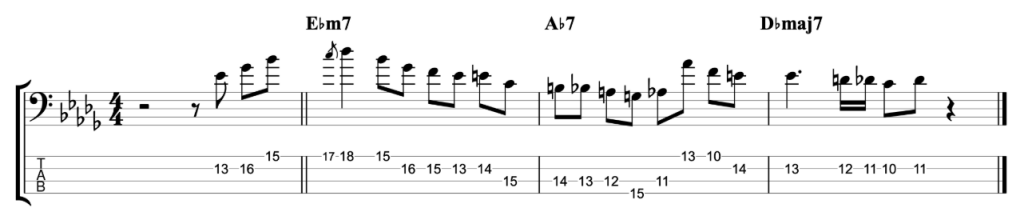

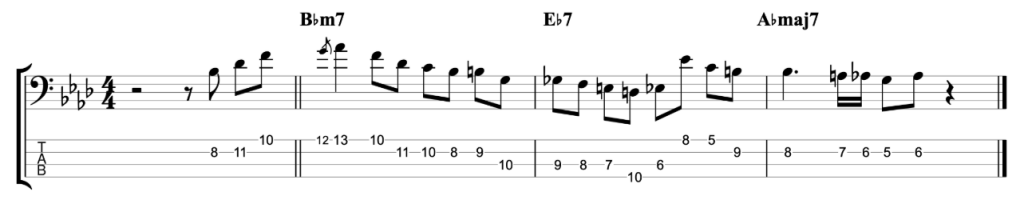

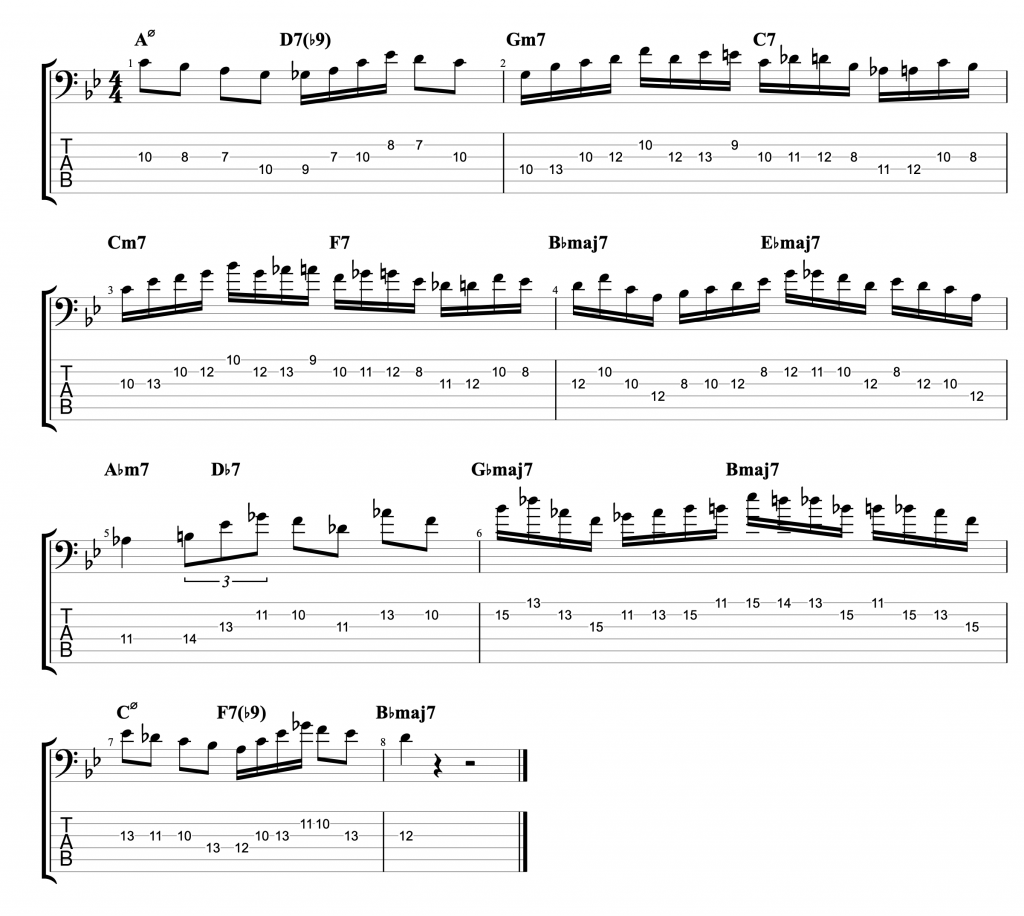

The fretless solo on top was just a bit of messing around. I added it to add some context to the bass line. I found while I was doing it that I had to concentrated really hard on where to start my lines. To make sure they came out in the right place harmonically. I’ve transcribed the solo too and here it is.

If you’d like to learn some more about playing bass lines in odd meters, then check out this link.