Triad Pairs – Part 3 – Triad Pairs & Hexatonic Scales on 6-String Bass – Bass Practice Diary – 18th February 2020

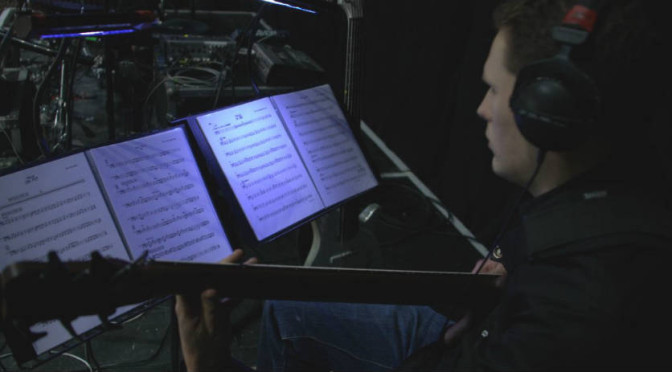

This week I’m exploring the connection between triad pairs and hexatonic scales. My two previous Triad Pairs videos have featured major triad pairs on 4-string bass. This week I’m opening it up to include all types of triads. And I’ve switched onto my 6-string bass because I would most commonly use these kind of ideas on my 6-string.

What are hexatonic scales?

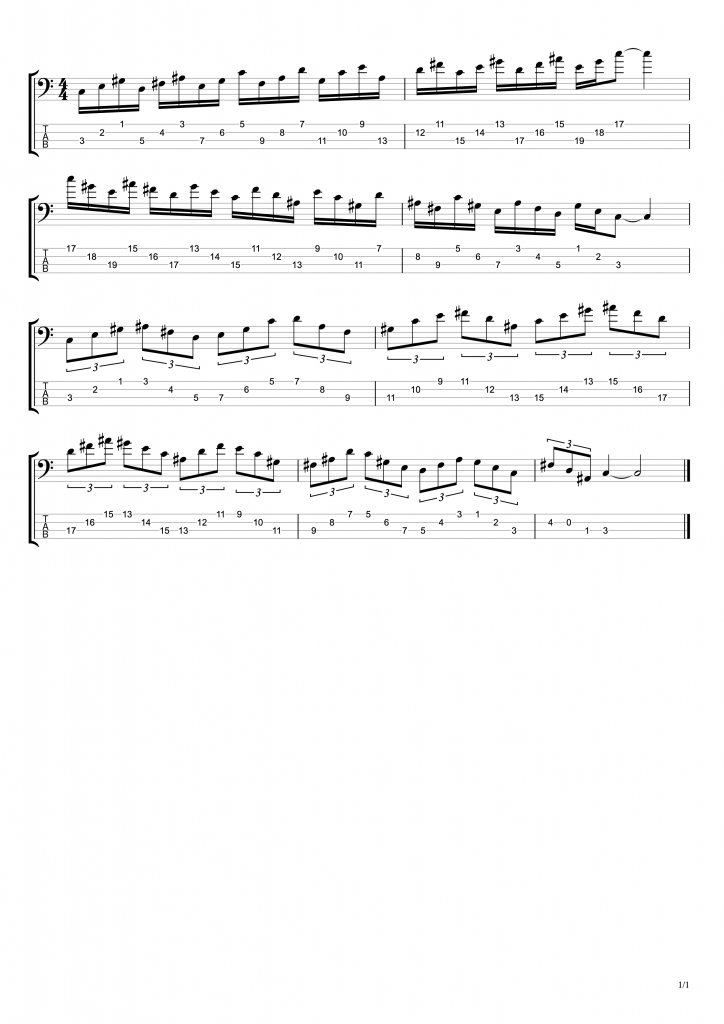

Hexatonic scales are simply scales that have six different notes. The term hexatonic doesn’t get used that often, except in the context of quite advanced jazz improvisation. But hexatonic scales are actually a lot more common than you might think. Probably the most obvious example of a commonly used hexatonic scale is the blues scale. Another common hexatonic scale is the whole tone scale.

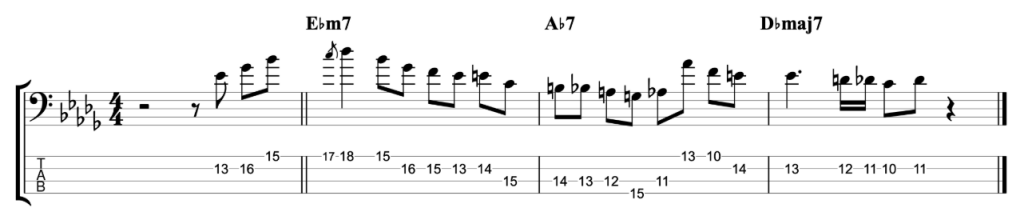

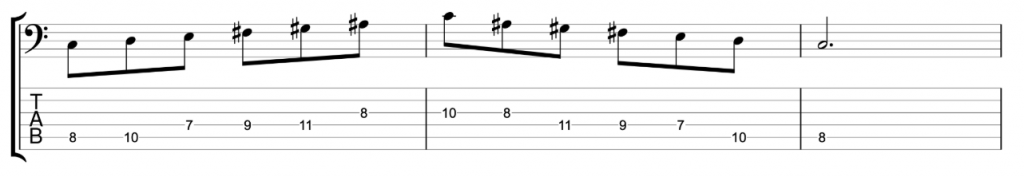

The C whole tone scale above is comprised of the notes of a C augmented triad and a D augmented triad.

Minor triad pairs

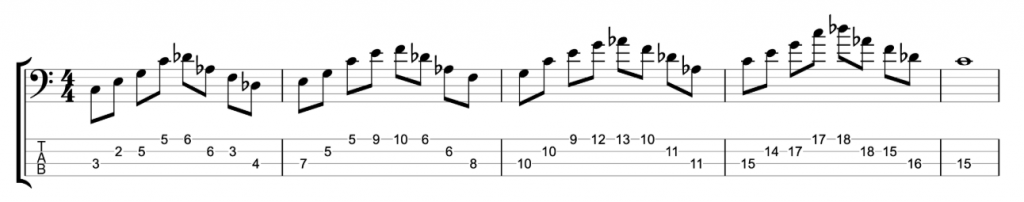

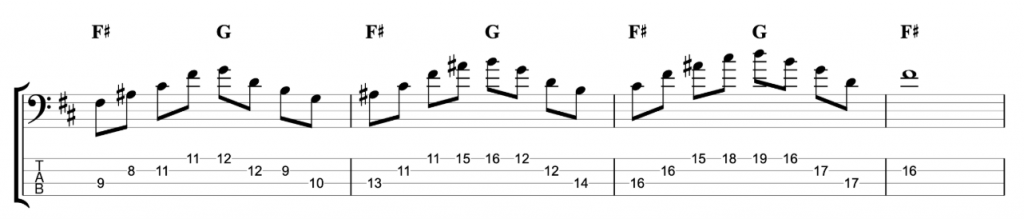

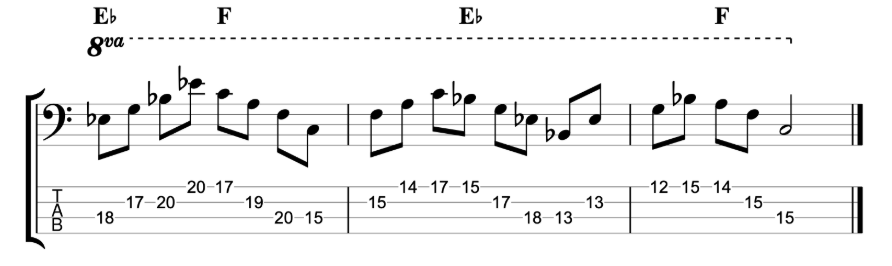

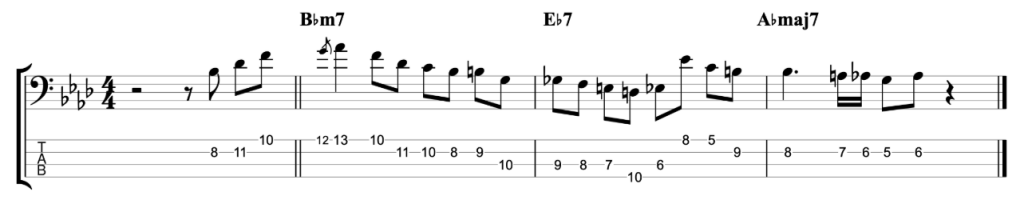

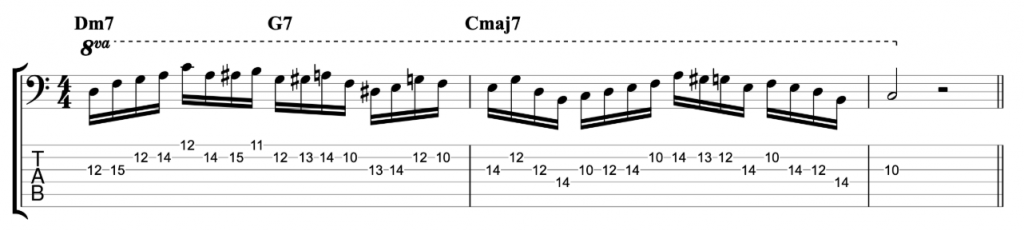

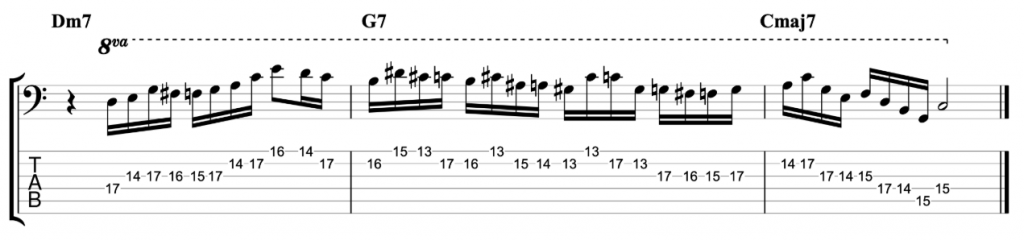

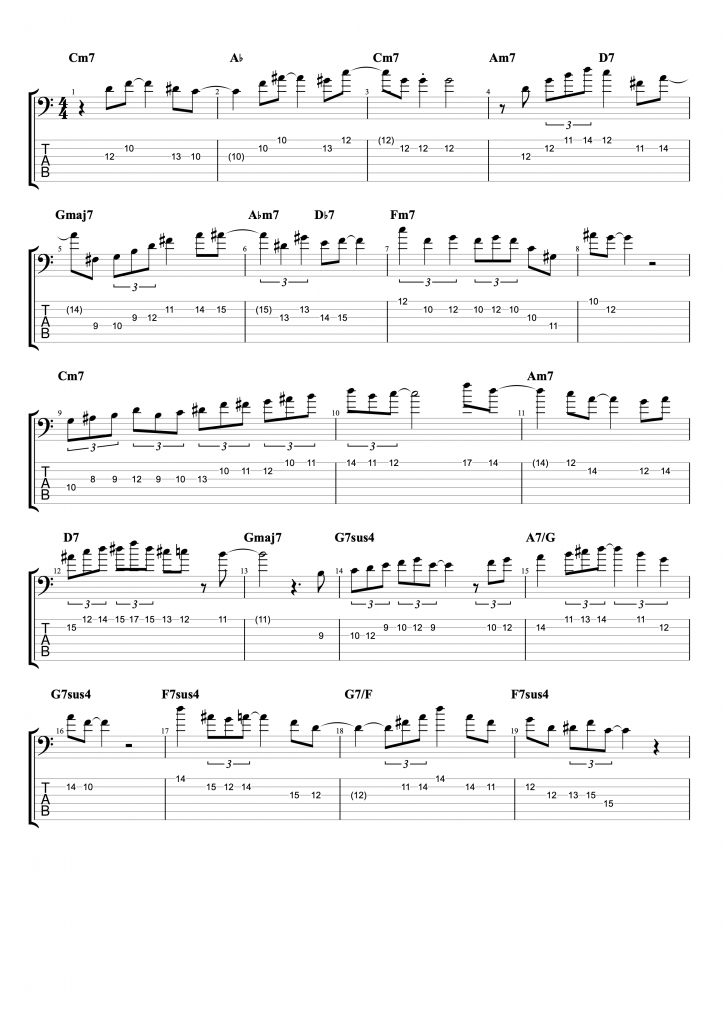

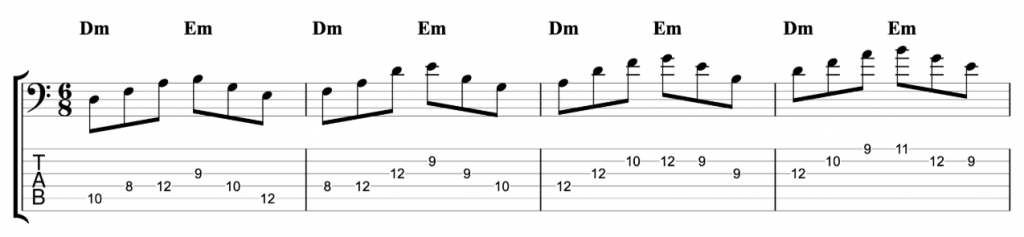

Having explored major triad pairs in my first two videos, the next most obvious triad pair would be two minor triads separated by a whole tone (2 frets). You can think of these as chords II and III in a major key. For example these two triads, Dm and Em, can be used to play lines in the key of C major.

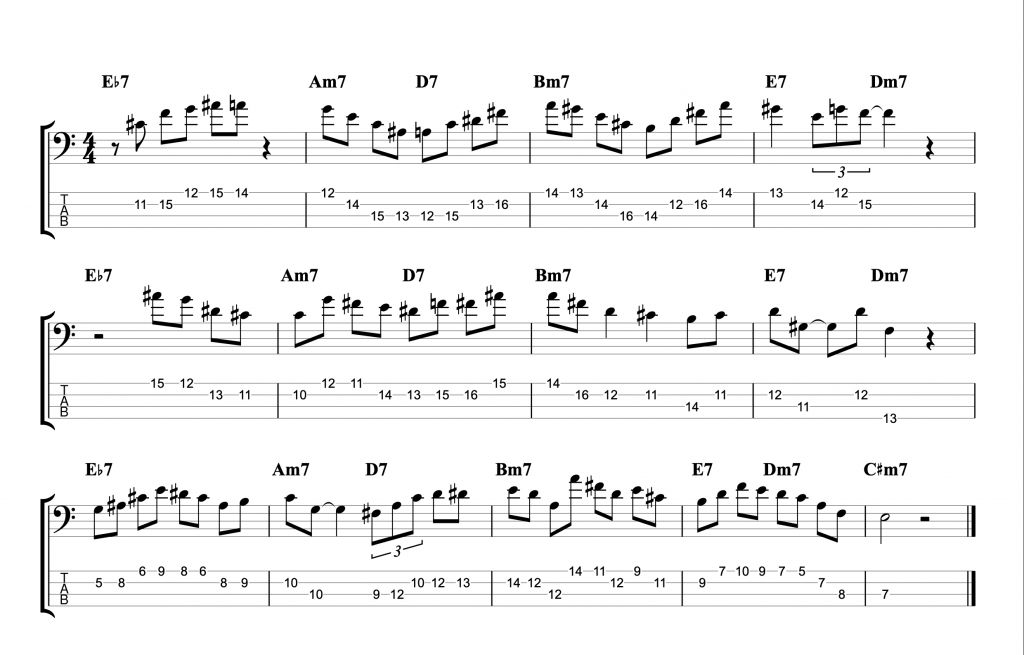

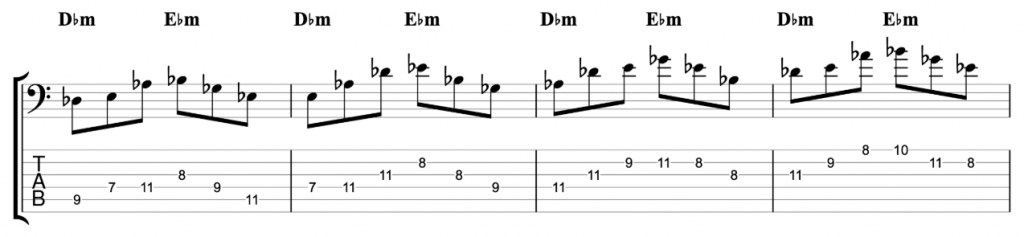

You can also find two minor triads a tone apart in the melodic minor scale. The altered scale is a mode of the melodic minor scale. I demonstrated in the video how you can create an altered scale sound on a C7 chord by using Db minor and Eb minor triads.

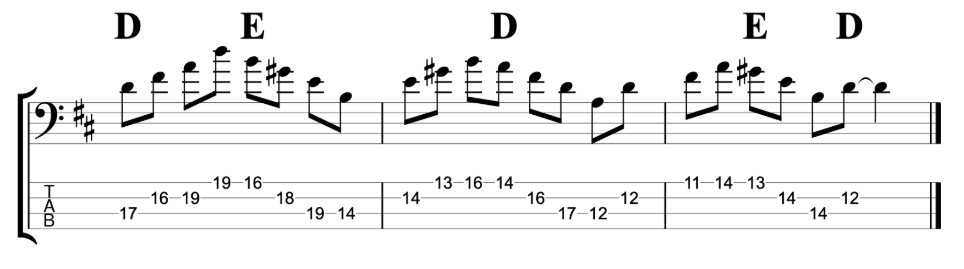

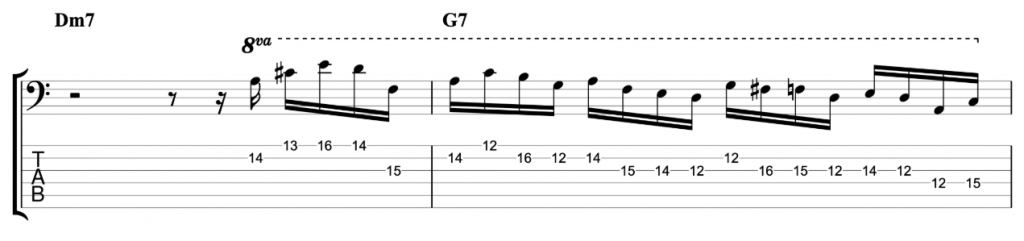

Combining different types of triads

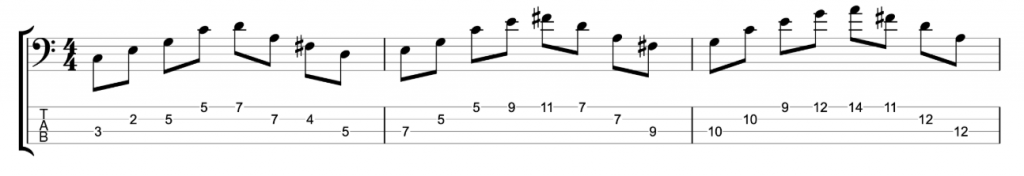

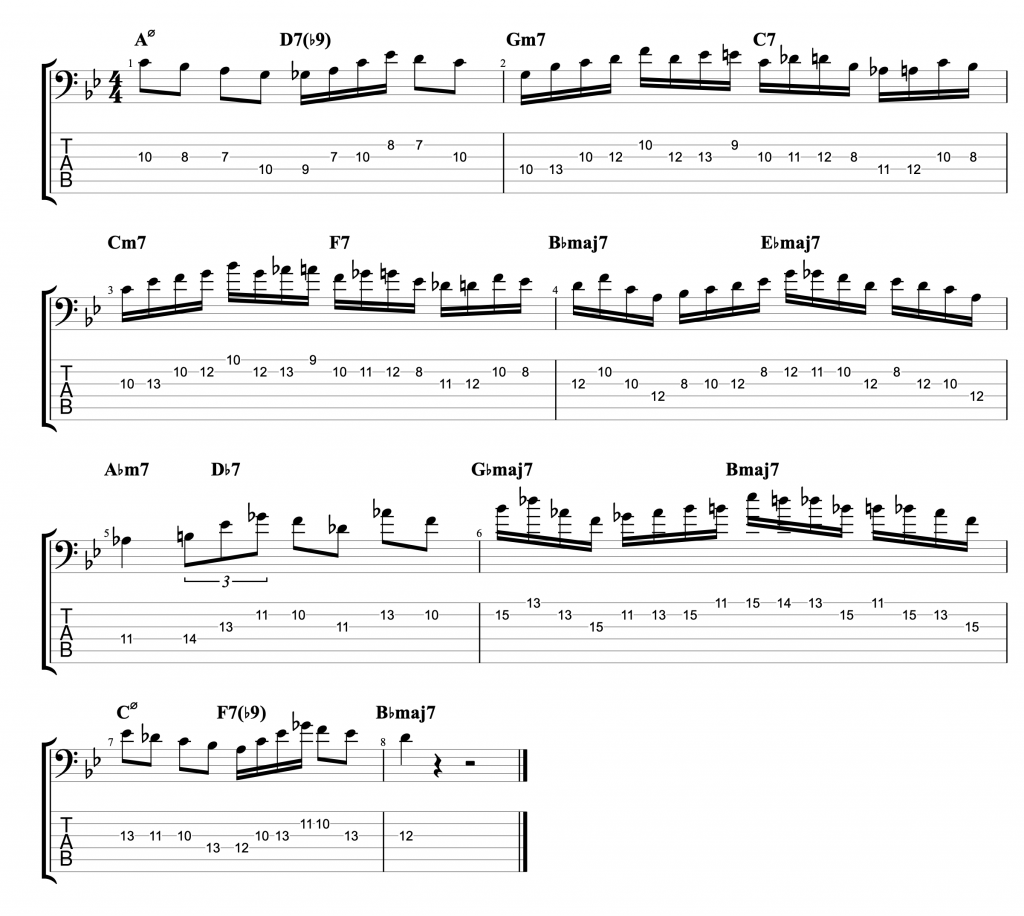

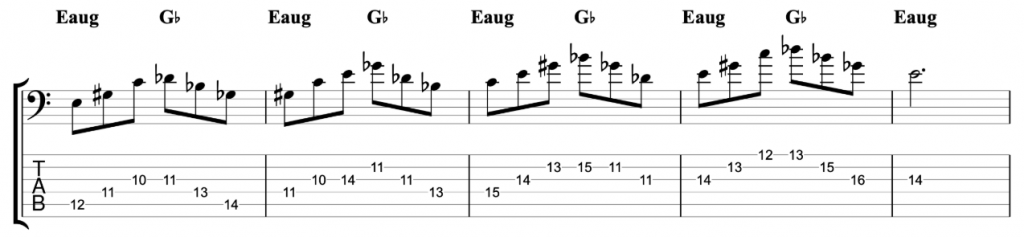

The idea of triad pairs, as I’ve mentioned previously, is to find two different triads that give you six different notes. Those two triads don’t have to be the same type of triad. In this next example, I’m playing an E augmented triad and a G major triad. This triad pair also creates an altered scale/melodic minor sound.

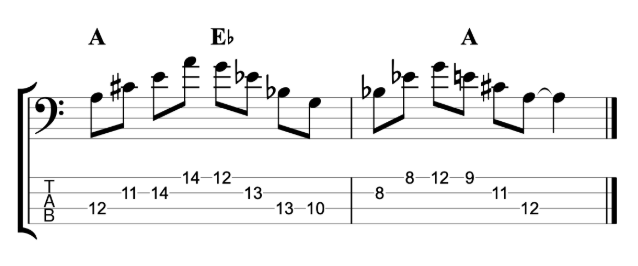

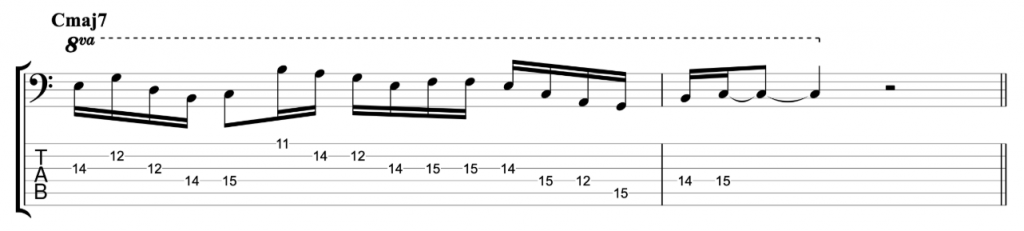

The Augmented Scale

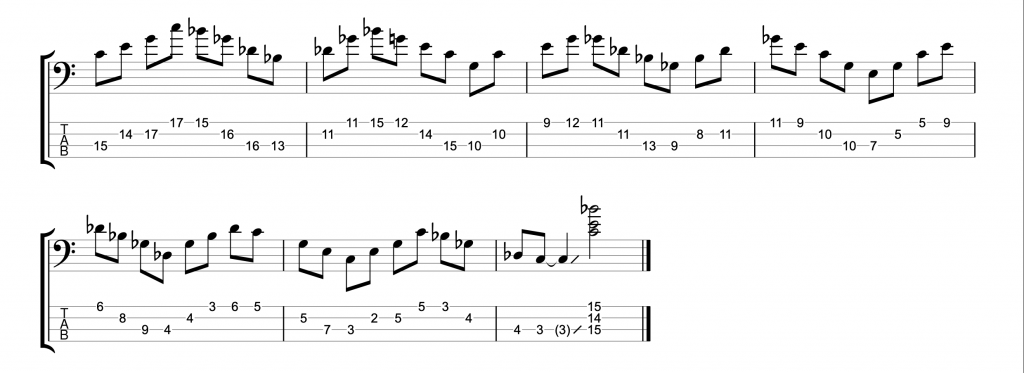

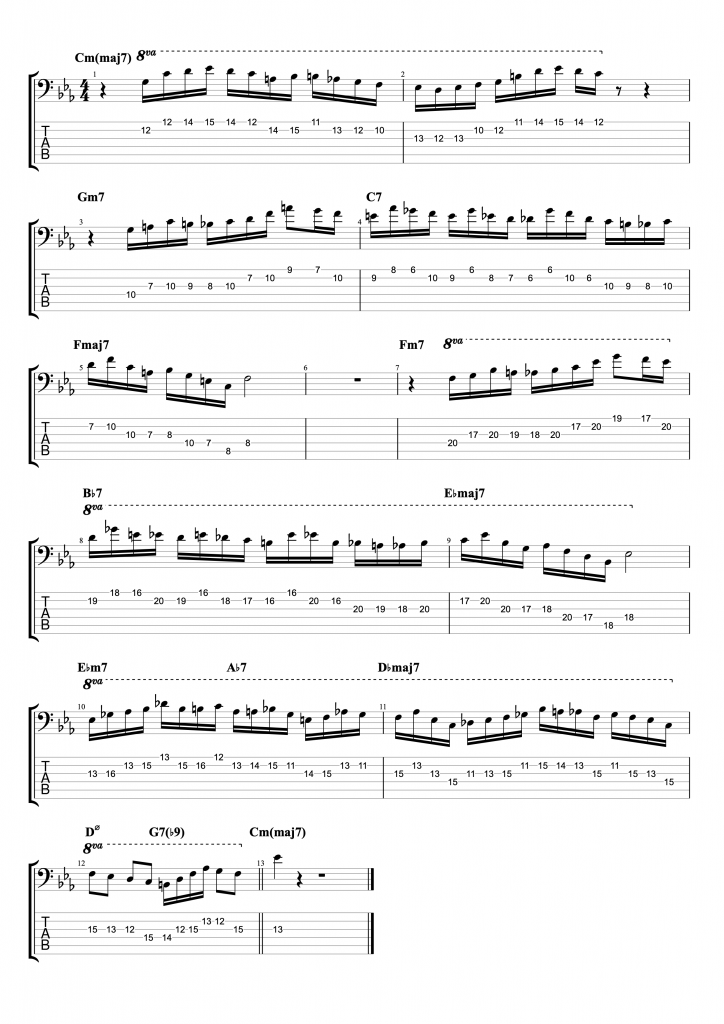

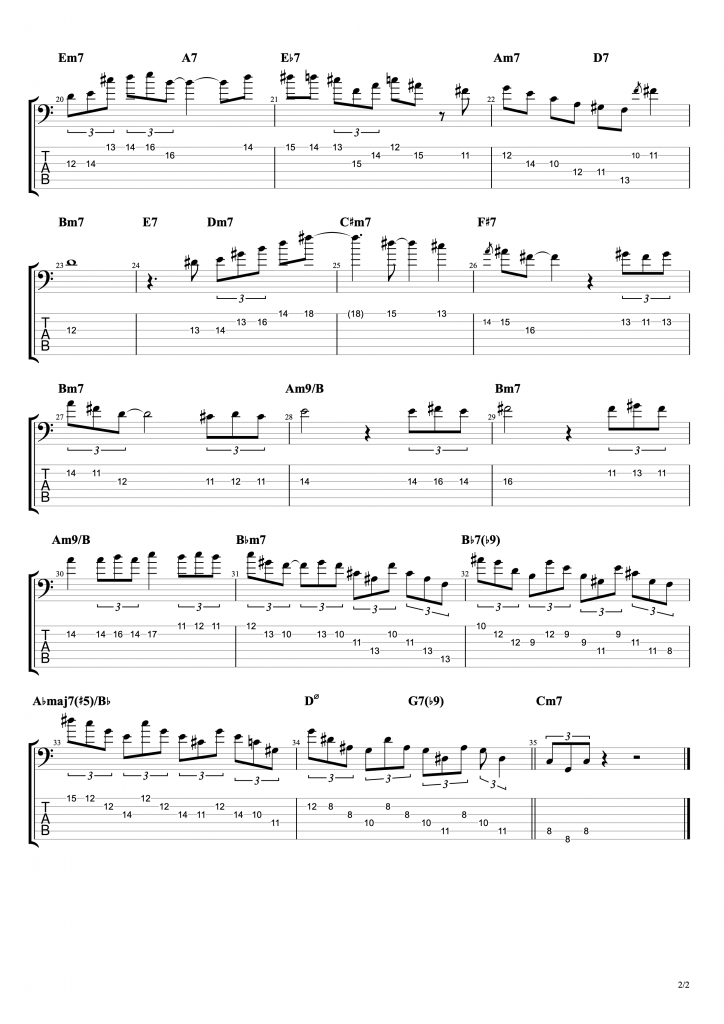

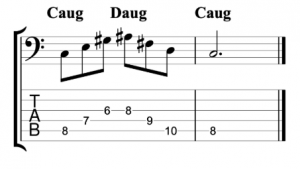

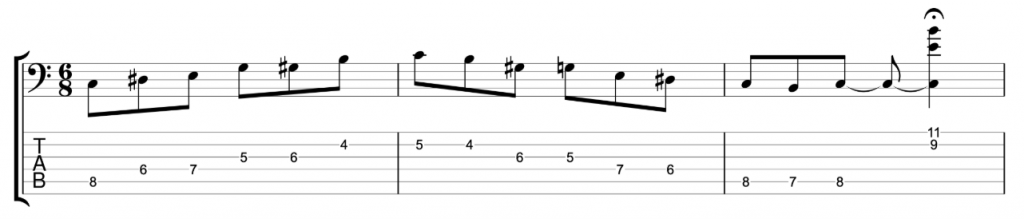

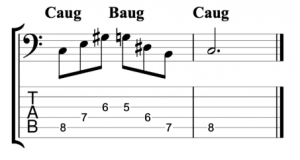

Another hexatonic scale created by combining two augmented triads is the augmented scale.

The augmented scale is comprised of the notes of two augmented triads a semitone apart. In this case, C augmented and B augmented.

These examples only scratch the surface of everything that you can do with triad pairs. Any time you can find two triads that give you six different notes, you have a triad pair. And those six notes can be played as a hexatonic scale. Practice my examples and see if you can find some more of your own.