Pentatonic Exercise for Bass Guitar – Bass Practice Diary – 7th May 2019

This week I’m featuring a pentatonic exercise. The reason that I’ve shared this is to show you how I approach practicing scales, or as I like to think of it harmony. I prefer not to use the word scale because it implies going up and down a pattern of notes. Whereas what I’m trying to achieve is learning how those notes fit all over the fretboard. And then coming up with different ways of playing them.

How to practice scales

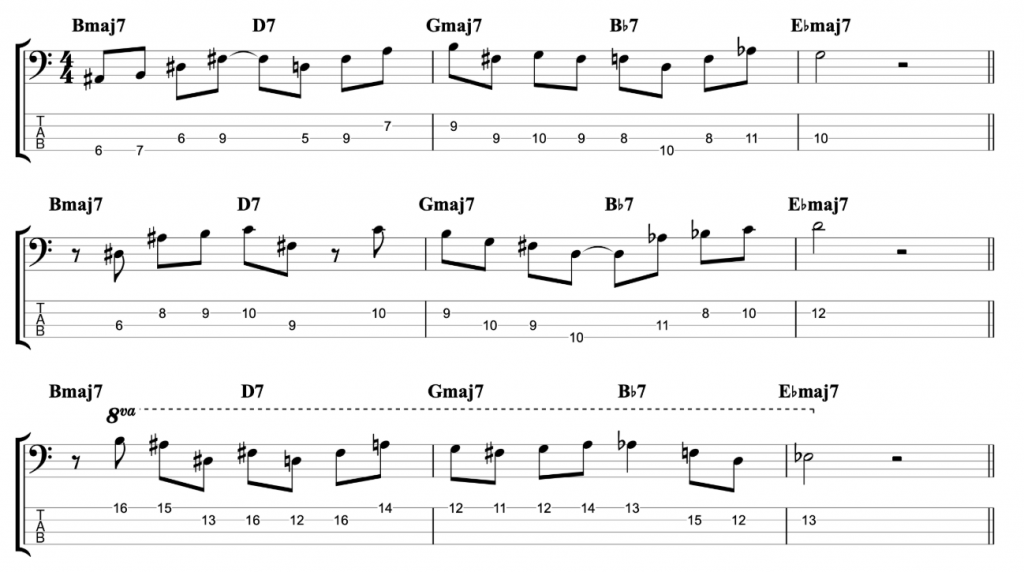

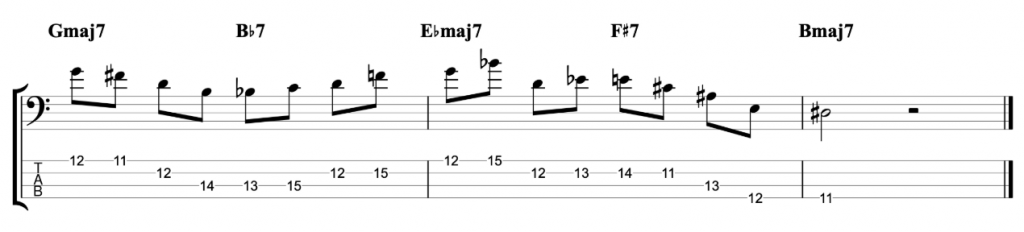

When I’m practicing a particular scale or harmony, I like to come up with new and different ways to move the harmony around the fretboard. The example in the video is just one example that I came up with. But in a single practice session I might come up with 5 or 6 different exercises using the same scale and practice them all for a few minutes each.

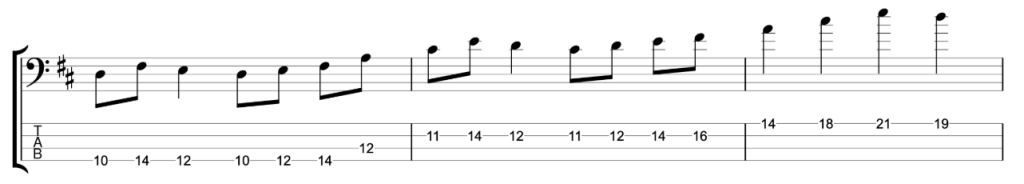

This works for any scale, arpeggio or melodic pattern. It’s the same process that I use when I’m practicing any harmony. I’ve used the pentatonic scale as an example because it’s simple and most people know it.

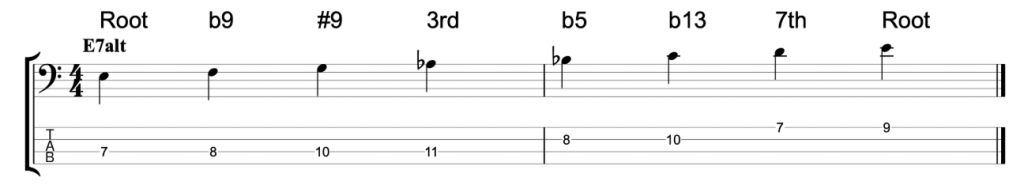

The pentatonic scale exercise with bass TAB

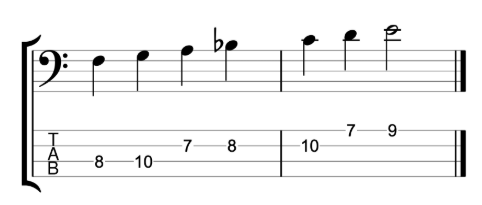

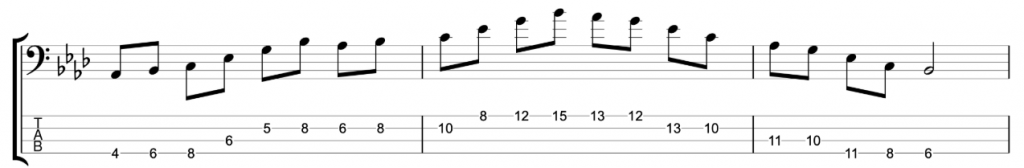

Here is the pentatonic exercise for bass written out as I played it in the video. I’ve used the root note G for both examples because the open string works well playing the root note. But you could adapt this exercise for any scale that has a G natural in it.

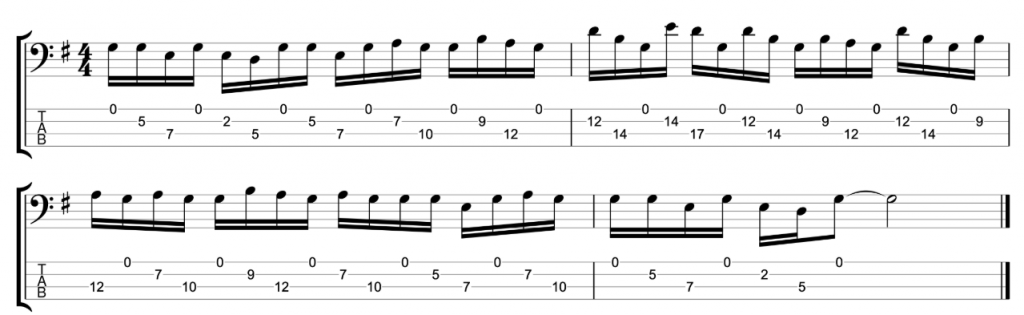

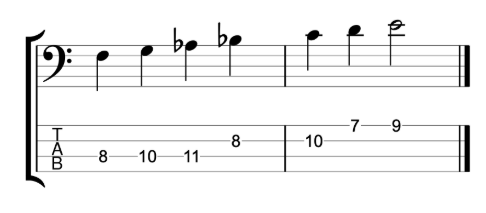

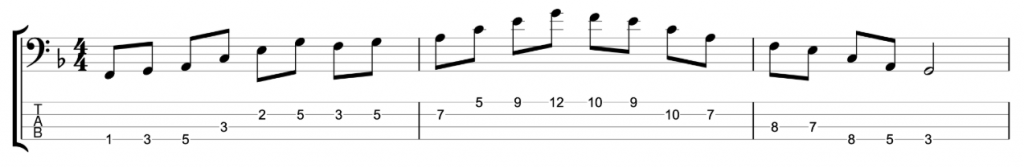

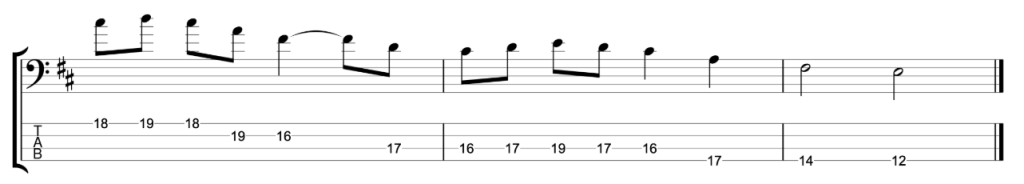

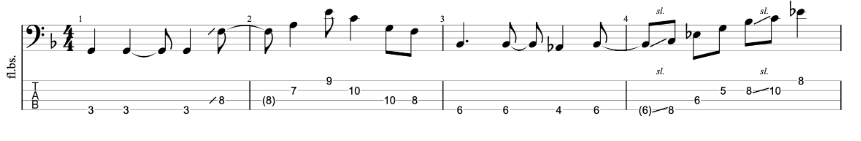

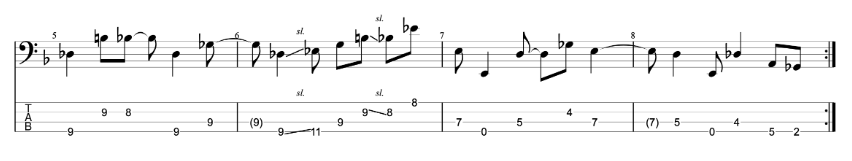

First, here is the G minor pentatonic exercise.

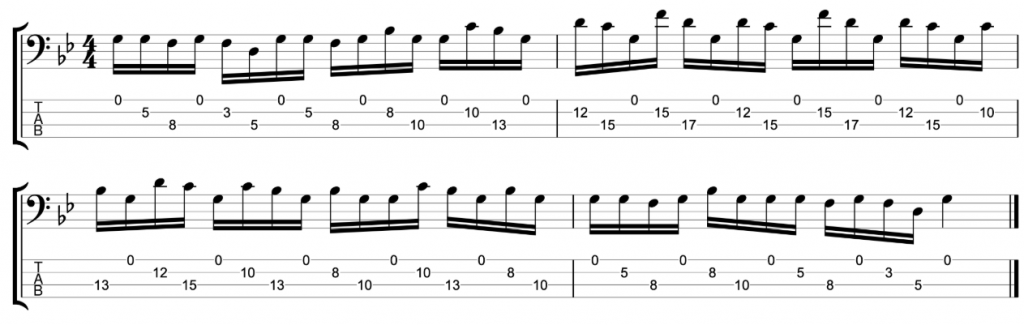

The exercise is simply a three note pattern that starts with an open string. The open string first string is always the first note of the three note pattern. But the other two notes move up and down the neck on the second and third strings.

The final element of the exercise is a rhythmic element. The three note pattern is played with a 1/16th note feel. Meaning that the emphasis keeps shifting onto a different 1/16th note each time you repeat the three note pattern.

If you’re not sure what a 1/16th note feel means, then check out my guide to 1/8th and 1/16th note feels here.

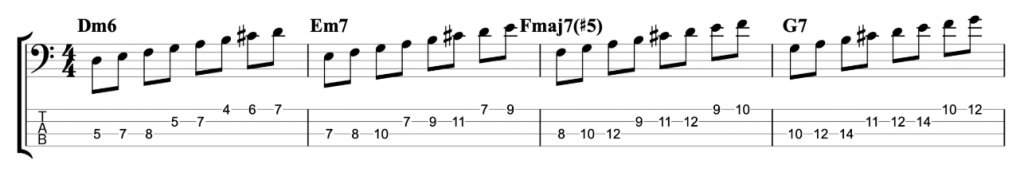

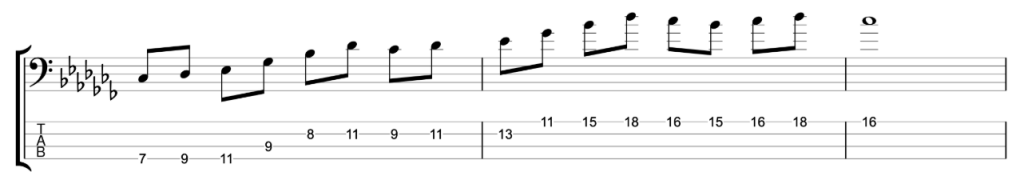

Finally, here is the same exercise adapted to the G major pentatonic scale.