Suspended and Major Chord Voicings – Bass Practice Diary – 31st July 2018

This week I’ve been looking for new and interesting chord voicings on my 6-string bass. Suspended chords tend to create a modern sound and I’ve demonstrated one particular voicing that I like and has proved to be quite versatile.

When I found this particular voicing I started moving it around to different positions and playing it over open strings, which created other chords, mostly major chords. What you see in the video is me improvising using this chord voicing.

It isn’t particularly structured practice, but that’s ok, because sometimes when you’re practising an impulse takes over and you just play for fun. That’s what’s happening in this video. And as soon as I’d shot the video, I pulled out my fretless Warwick Thumb SC to play a bit of melodic improvisation over the top.

If you’re interested in that kind of melodic improvising with fretless bass then check out these two recent posts. Use Fretless Bass to Play Jazz Solos and Melodies and Charlie Parker Tunes on Fretless Bass Guitar.

What Are Suspended Chords?

Suspended chords or sus chords are chords that omit a third in favour of using either the second or fourth or both. The absence of a third makes the chords neither major or minor. It’s the third that defines whether a chord is major or minor. And sus chords have a neutral sound as a result of not having a third. Listen to Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage for an example of the suspended chord sound being used in jazz.

The chord symbol for a C suspended chord can be written as Csus. I sometimes see it written as C11. I don’t like the 11 chord symbol because, although a 4th is the same as an 11th, the 11 chord symbol implies to me the presence of a third, dominant seventh and a ninth. So the sus symbol is more accurate.

Csus2 is C, D and G (root, 2nd, 5th), Csus4 is C, F and G (root, 4th, 5th). You can think of C7sus as Bb/C. The Bb, D and F from the Bb major triad function as the dominant 7th, 2nd and 4th and create a suspended sound when you play them over a C root note. You could also call the same chord C9sus because the 2nd and 9th are interchangeable in the same way that the 4th and 11th are.

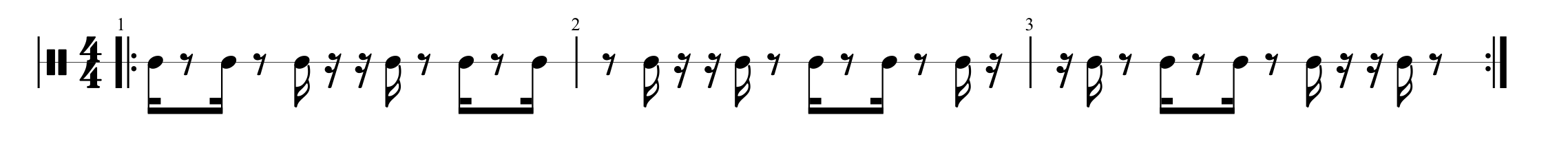

The Opening Chord Sequence

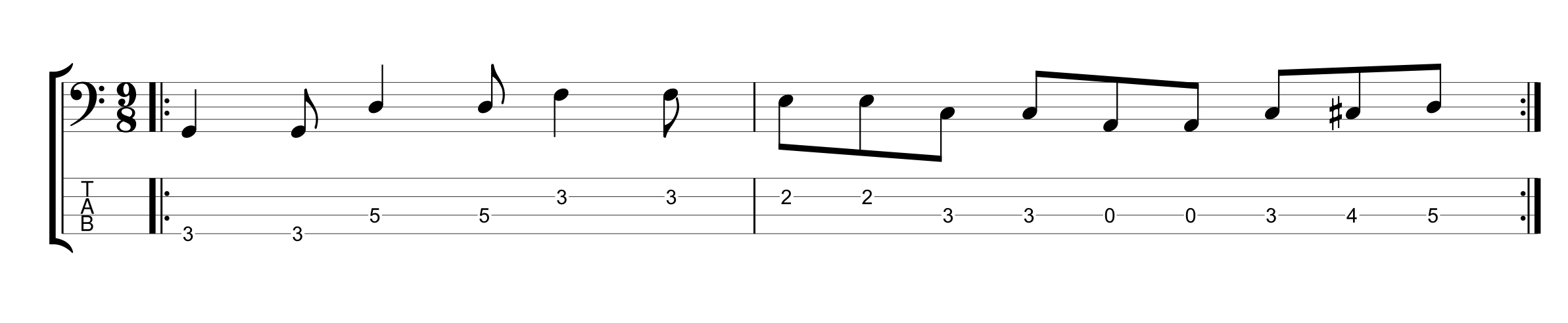

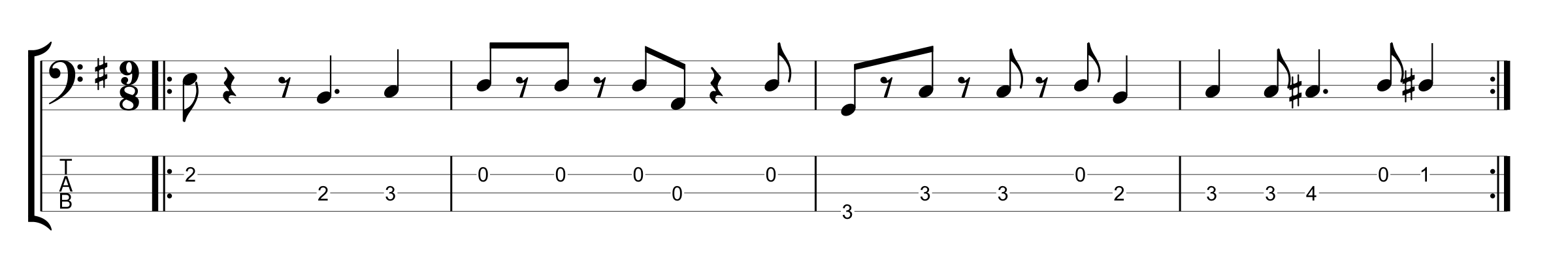

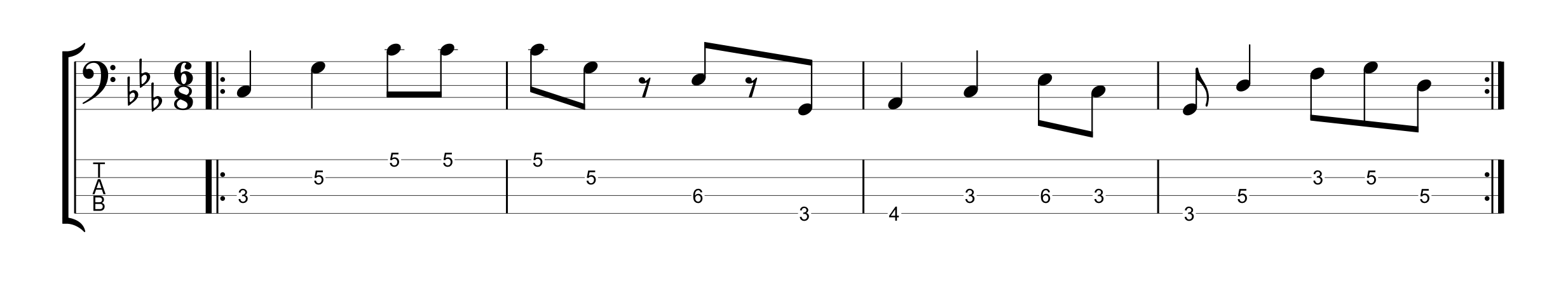

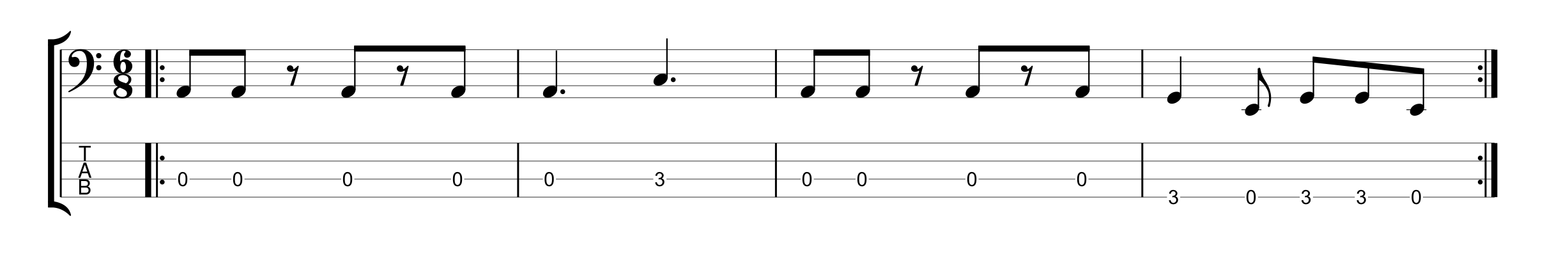

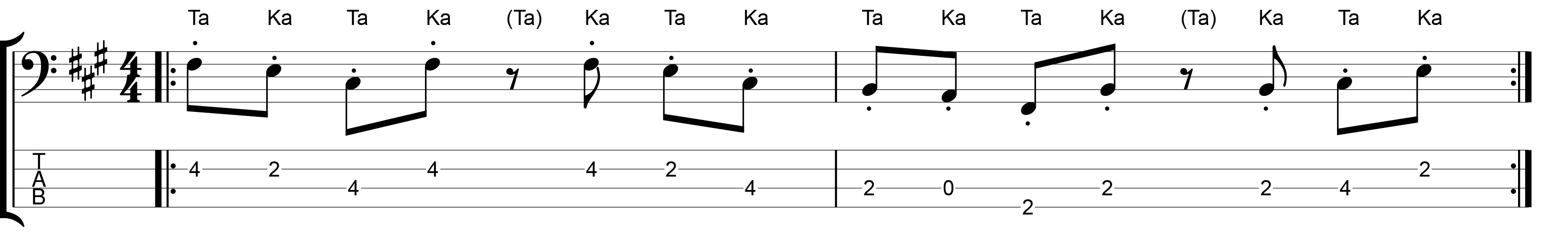

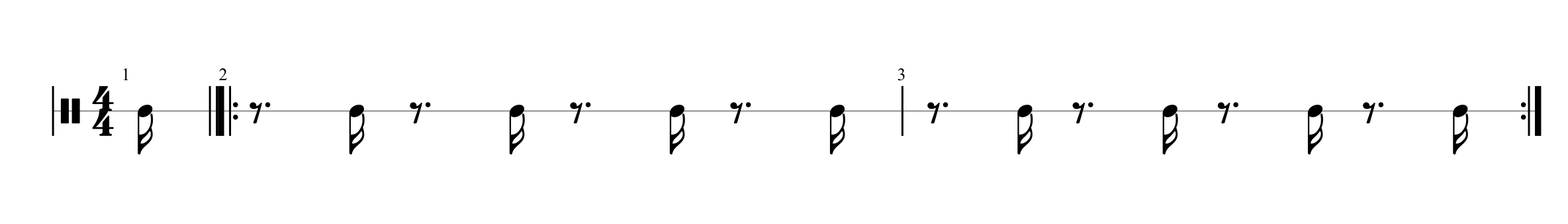

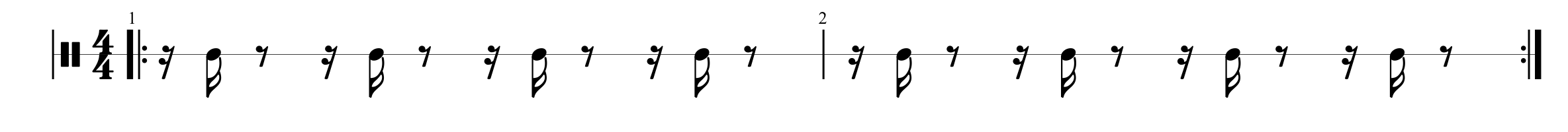

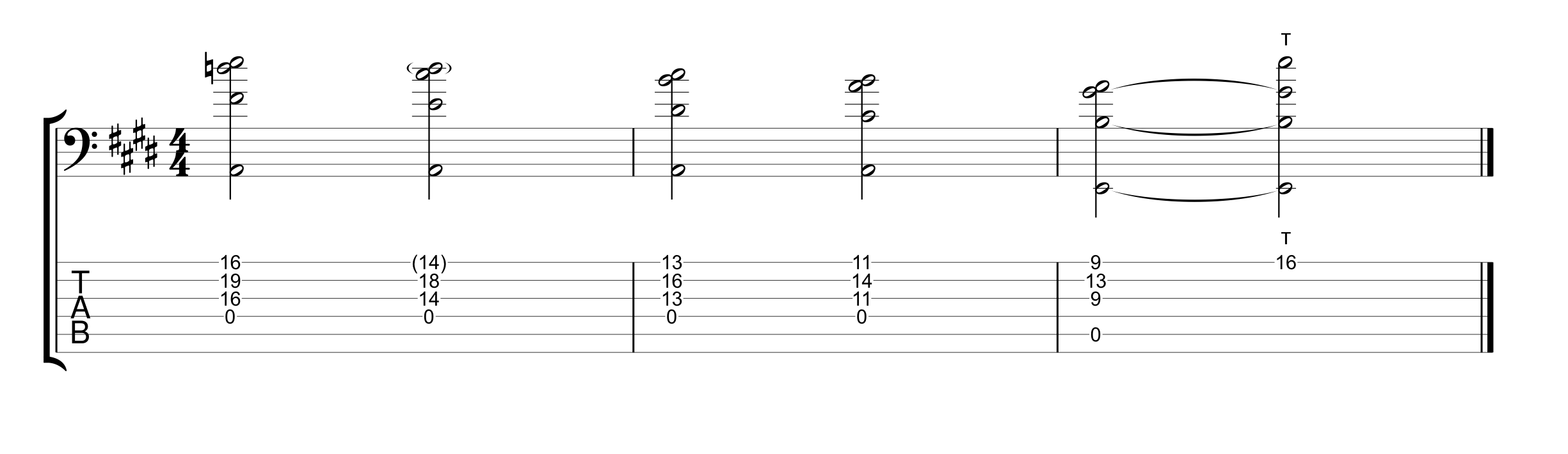

The opening sequence in the video is played over an open A string until the final chord which is played over an open E. All of the voicings are built by playing an interval of a sixth between the D and G strings, and an interval of a second between the G and C strings. Try making your own chords using the same voicings. You can adapt them onto four and five string basses by playing over the open E string and voicing the chords on the A, D and G strings.

Due to the improvised nature of my performance in the video, many of these chords are no longer sus chords. Many of them are major chords. What started off as an exercise in finding suspended chord voicings became an improvisation using the same chord voicing against open strings.

The Chord Theory

The first chord in the opening sequence is a suspended chord, but the second has a major sound. It contains a C#. Which is the major 3rd of A. If you listen carefully in the video I don’t play the top note on the second chord. It would have been a D. I was improvising and I’ve no idea what I was thinking in the moment. But I may have thought that C# and D would clash, being a semi-tone apart. In hindsight I slightly regret this. Conventional jazz theory says don’t include a major 3rd and natural 11th in the same chord voicing. But I think it works in this context. So I’ve included the note in the TAB even though it’s not in the video.

The third chord creates a lydian sound with the sharp 11th D# and major 3rd C#. You can check out my video on lydian sounds by clicking here. The fourth chord creates a straightforward A major sound with an added 9th. And the final chord creates an E major/Esus sound. Again, I’ve included the major 3rd and natural 11th, which I think sounds cool. Even though the two notes clash if you play them simultaneously. Notice that I’ve finger picked each note individually to cut down on the impact of such clashes. The final note that I’ve included is tapped with my right hand index finger.

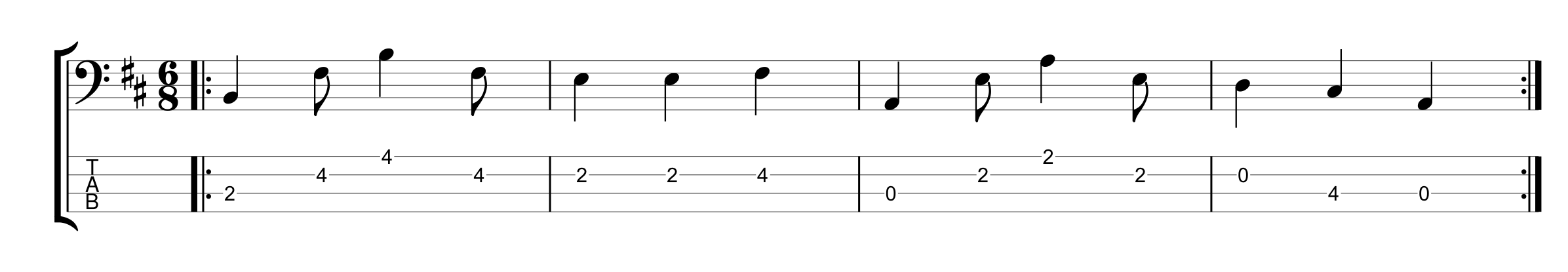

The Closing Sequence

The closing sequence simply uses the last two chords of the opening sequence and repeats them. I hope you have some fun with these chord voicings and you’re able to come up with some original chords.