Inside and Outside Notes – Start Using More Outside Notes in Your Bass Lines – Bass Practice Diary – 28th August 2018

Recently I made a video called Everything You Need to Know About Harmony on Bass Guitar. You can check it out by clicking on the link. In the video I talked about using inside and outside notes. Well I thought it was time for a practical video about how you can practice playing inside and outside notes. Here it is!

Inside and Outside Notes

The simplest way to explain inside and outside notes is that inside notes are notes that belong in the key you are playing and outside notes don’t. Hopefully you know already that I don’t believe there is any such thing as “wrong” notes. Simply because outside notes can make your basslines more interesting when they’re used in a musical way. You can use them to create tension within music, which is very hard to achieve if you only play inside notes. And the resolution of those notes onto inside notes creates a resolution of the tension.

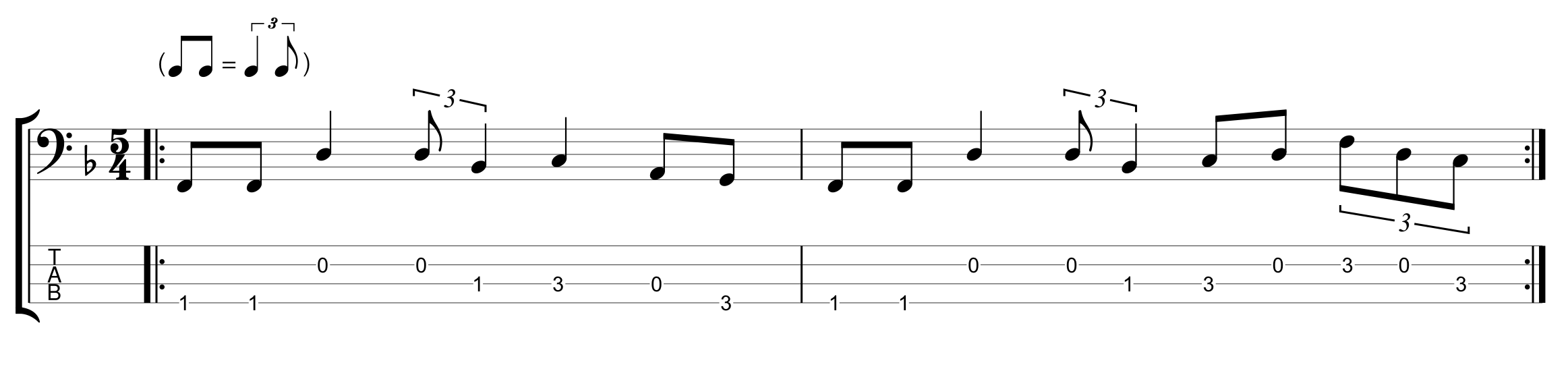

How Can You Practice Using Outside Notes

This video is a practical guide not a theory lesson so I’m going to jump straight in to the musical examples. If you’d like to learn more of the theory then jump to my previous video which is linked in the opening paragraph.

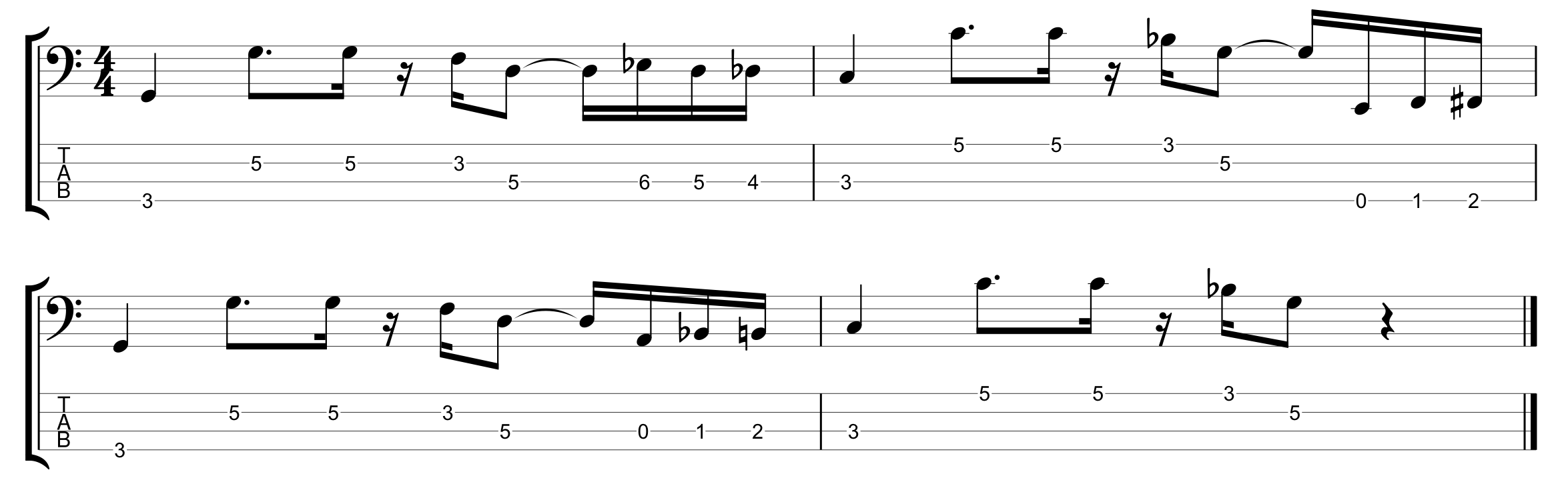

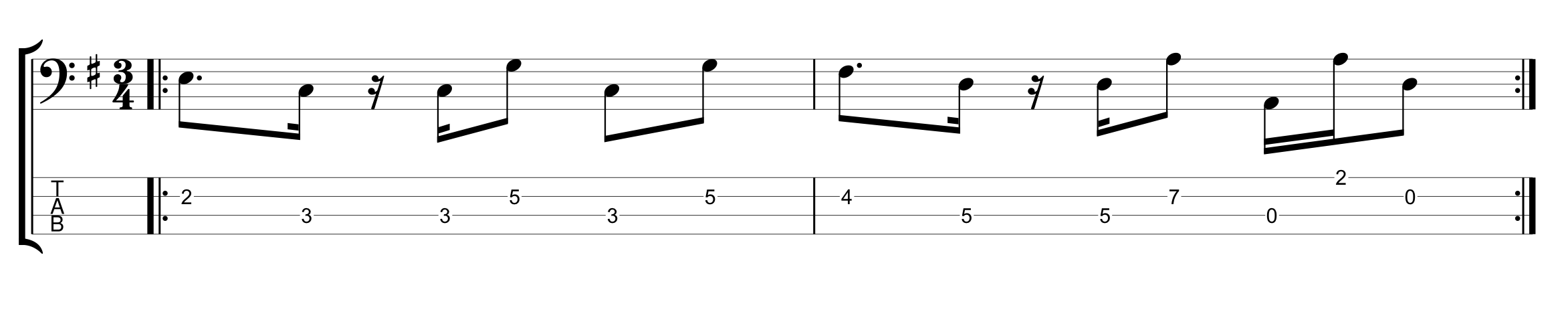

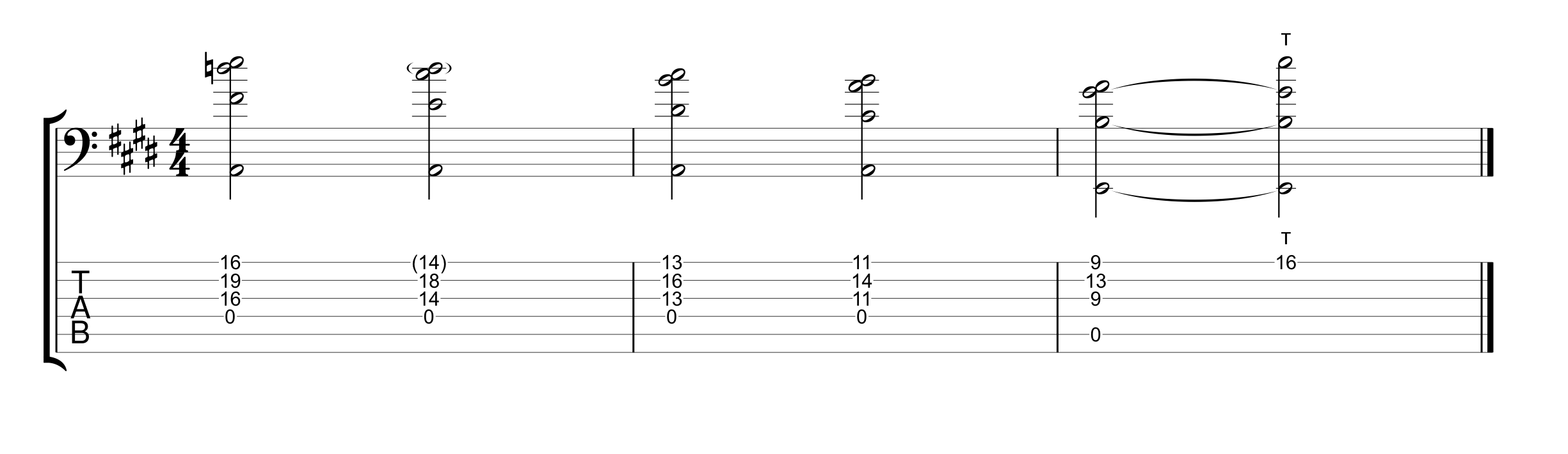

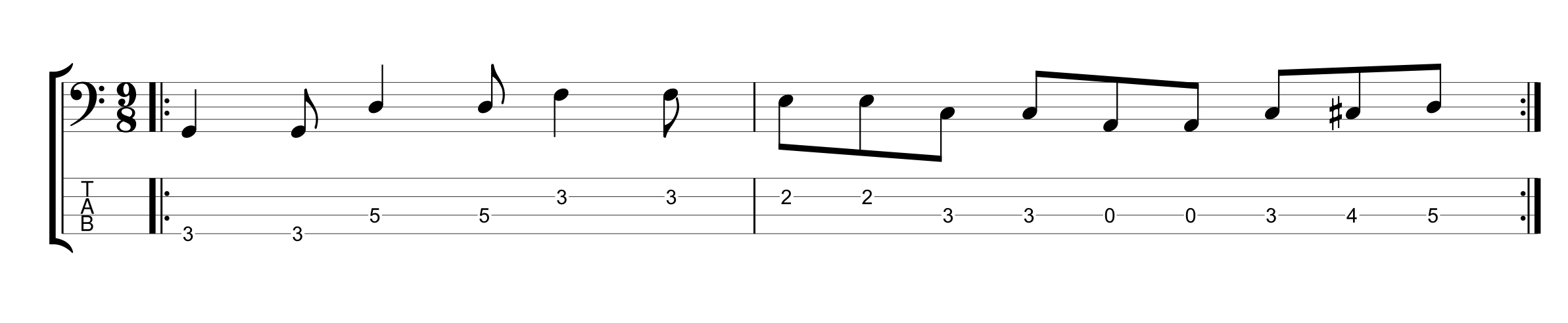

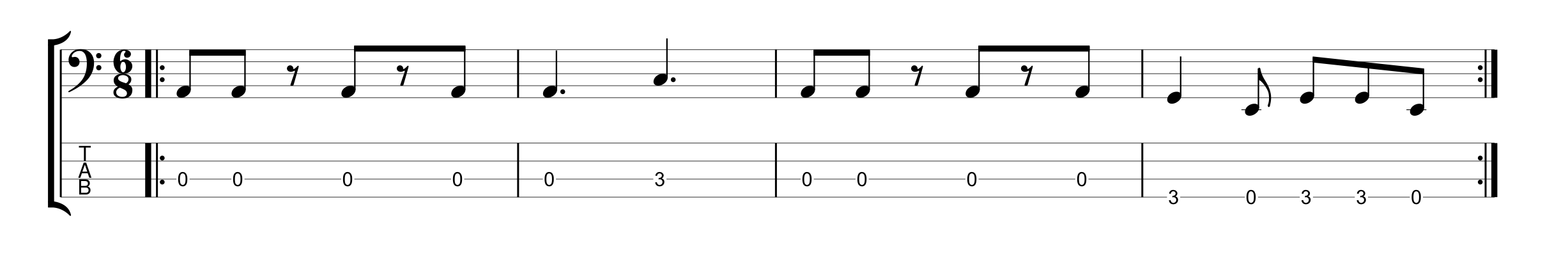

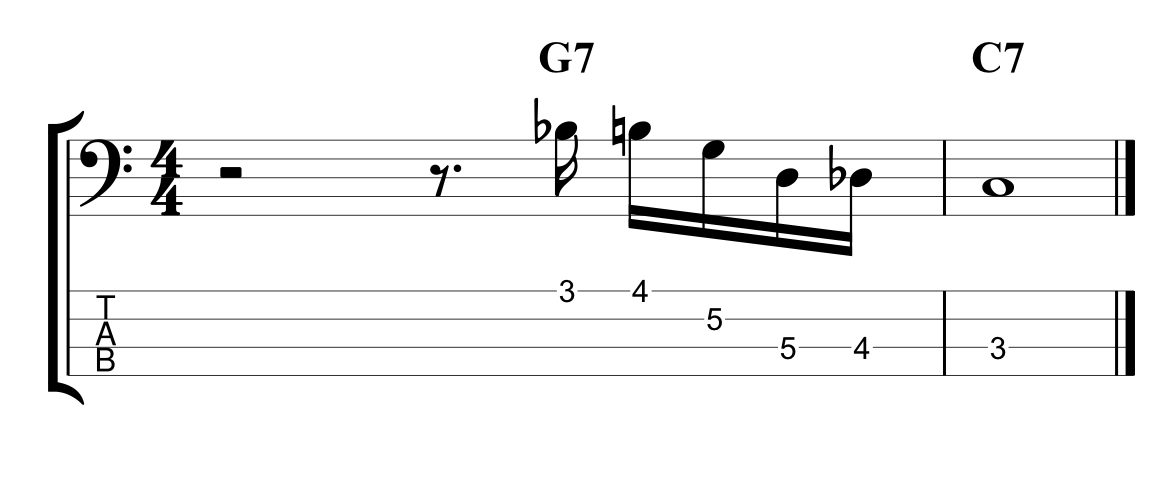

I started with two chords, G7 and C7. And I created a bassline using only chord tones. The notes are G, B, D and F for G7 and C, E, G and Bb for C7.

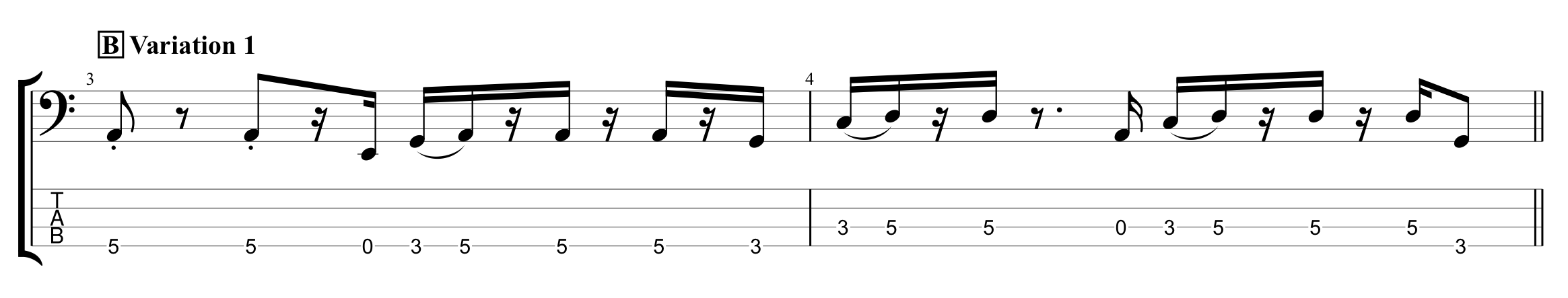

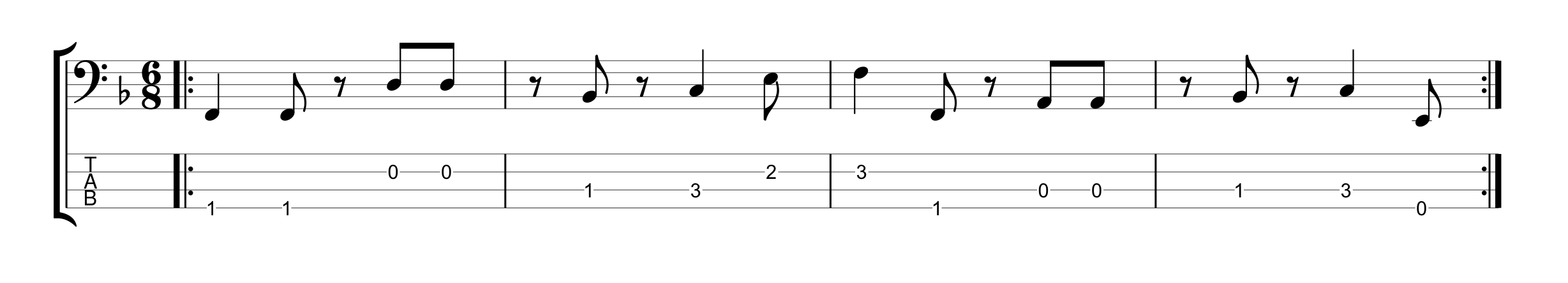

The first variation I played was to add a note one fret above or below either of the root notes. In the following example I’ve added the note Db before the C root note and Ab before the G root note. Both Db and Ab are outside notes on both G7 and C7 chords.

Notice that these notes always resolve onto the root note. Meaning that the next note after the outside note is always the root note. It’s that resolution that keeps the outside notes from sounding “wrong”.

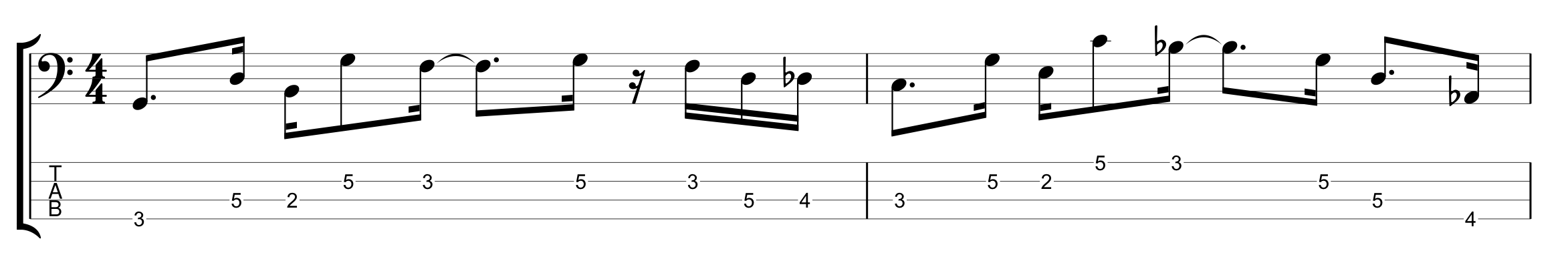

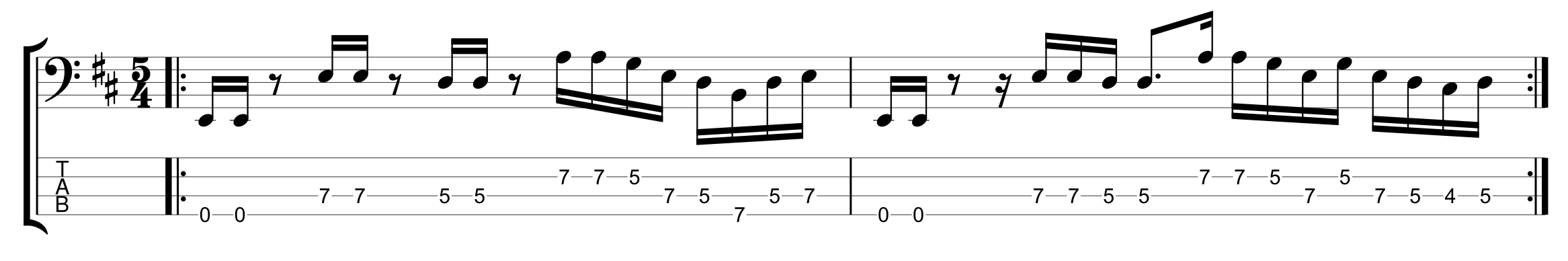

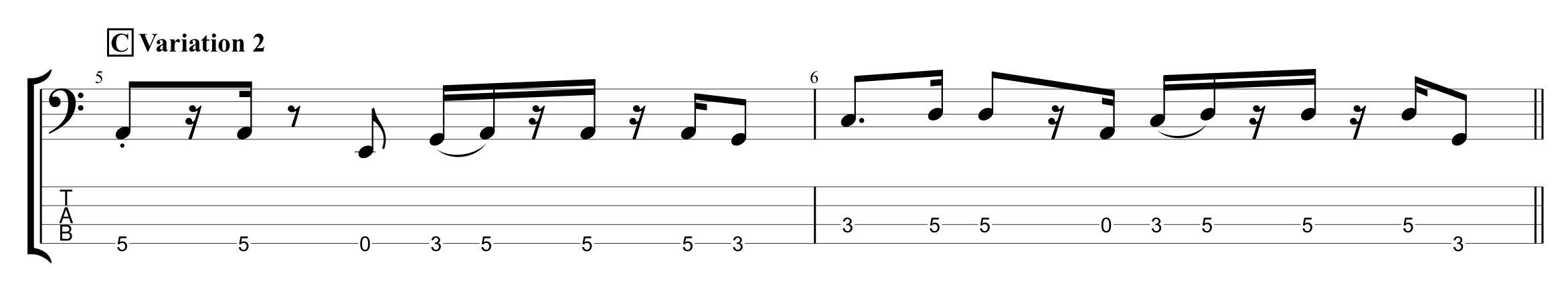

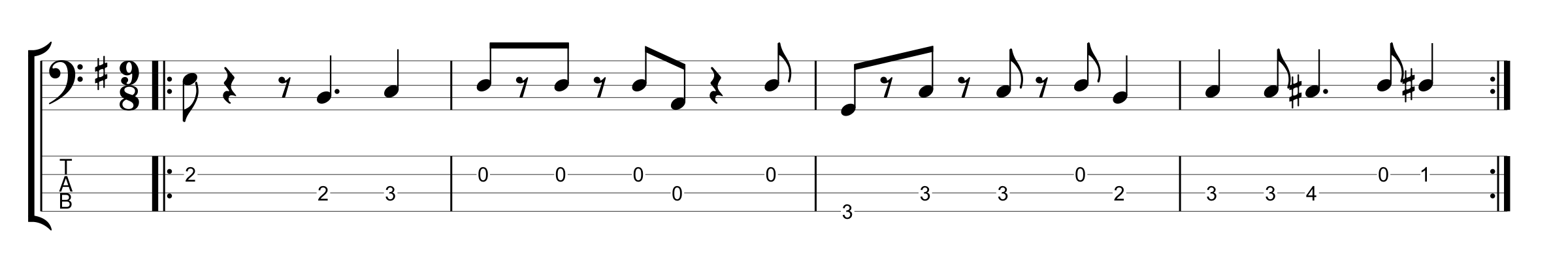

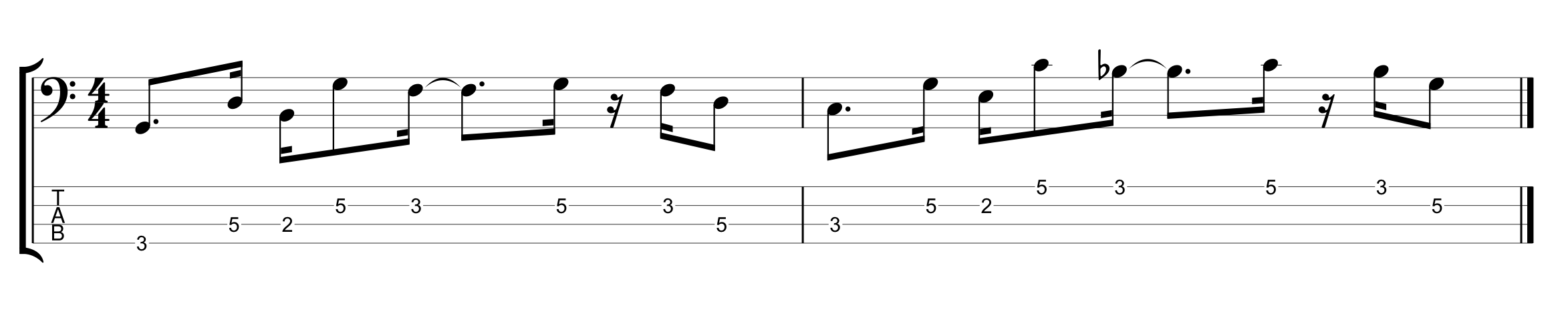

Resolving Outside Notes Onto Chord Tones

You can resolve outside notes onto any chord tone. It doesn’t have to be the root. The following example starts on a Bb, which is an outside note on G7. The Bb resolves up one fret onto B natural which is a chord tone. The next outside note is Db which resolves onto the root note of the next chord C7.

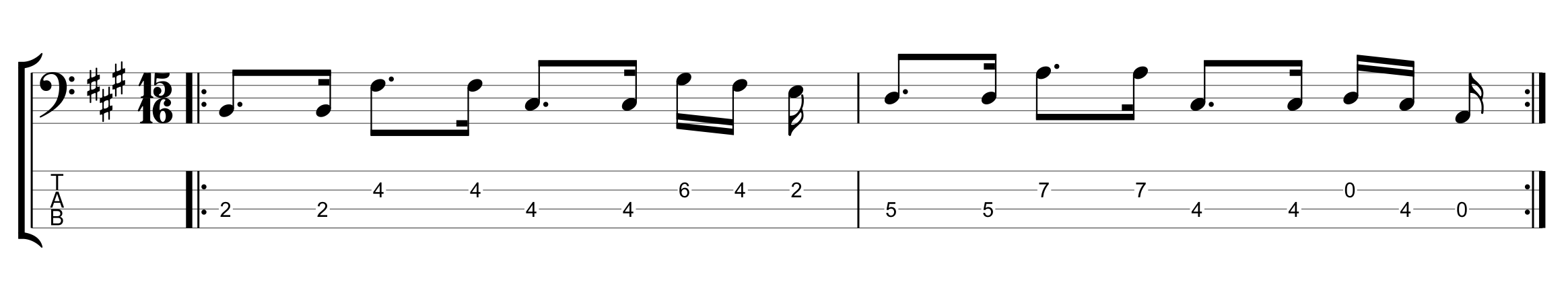

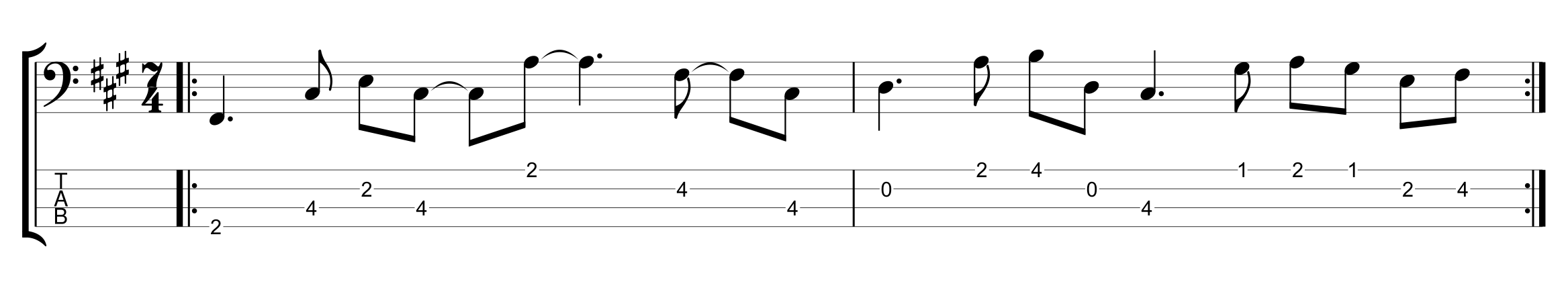

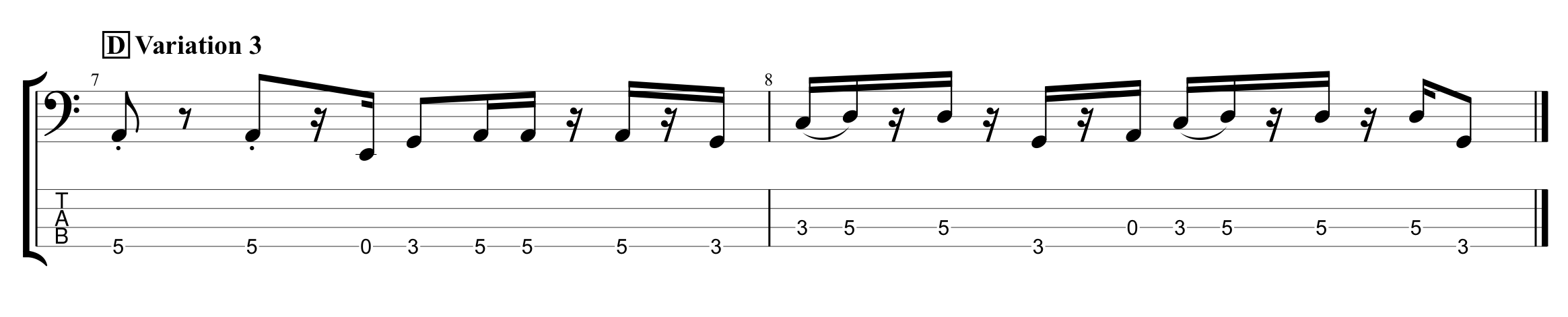

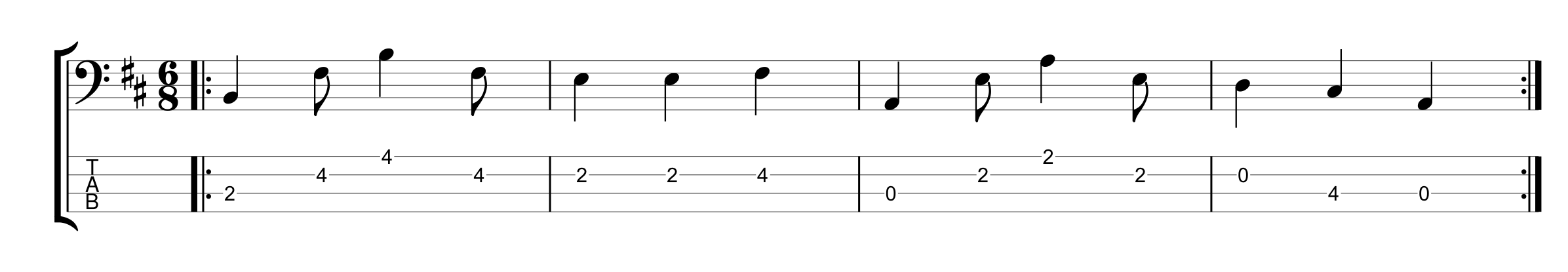

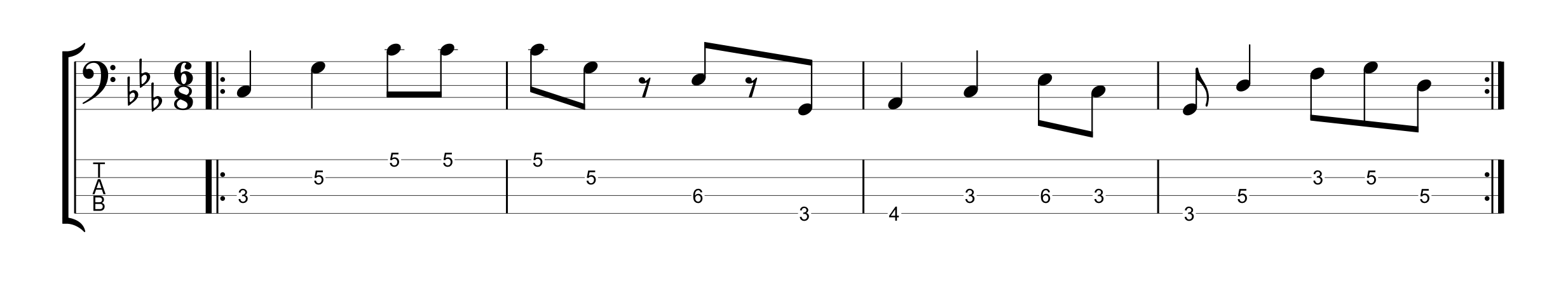

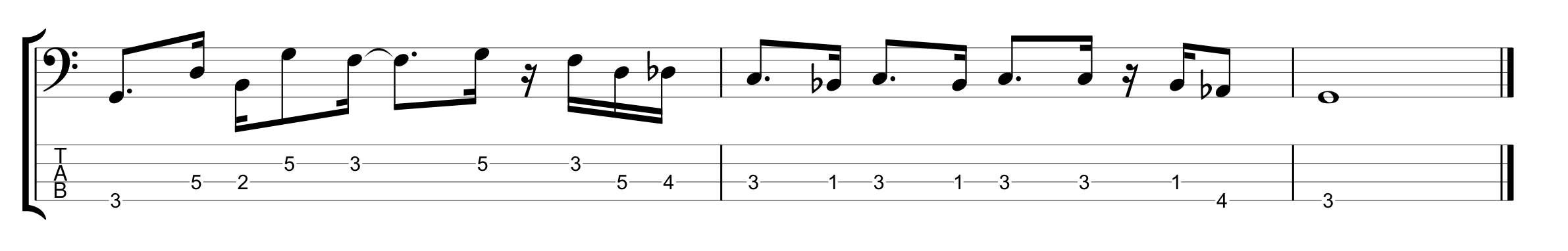

Chromatic Runs

The final technique for incorporating outside notes that I looked at in the video is chromatic runs. I usually use these when leading into a chord change.

Starting three frets either above or below the root note, simply play each fret either up or down to the root. It’s a simple technique, but it sounds cool if you don’t over use it. The following bassline demonstrates the technique.