In Part 4 we’re going to look at chord extensions.

In this video lesson you’re going to learn how to play chords with chord extensions on the bass. I’ll also explain what notes you can leave out and why, in order to make your chords sound more interesting.

What are chord extensions?

Extended harmony is where chords get a lot more interesting sounding but it’s also where the theory gets more complicated. Chord extensions are notes that we can add to basic chords like triads. Having established how to play triads in Part 3, we can now look at adding chord extensions to them.

The most common chord extension by far is the seventh. In Part 3 we looked at how triads are made up of a root, a third and a fifth. And there is an interval of a third between each of these notes. In order to make a triad into a seventh chord we just continue this pattern of stacking intervals of a third. We add a note that is a third above the fifth and we call this note the seventh. Seventh chords have four notes in them root, third, fifth and seventh.

Four types of seventh chords

If you watched my video about “Intervals” then you’ll know that there are two types of sevenths, major and minor just like there are major and minor thirds. Fifths however are not major or minor and so the fifth is the same in both major and minor chords. For this reason, it’s the third and seventh notes of each chord that define what type of chord it is.

For example if you have a chord with a major third and a major seventh in it, it’s called a major seventh chord and a chord with a minor third and a minor seventh is called a minor seventh chord. The word used to describe a chord that has a major third and a minor seventh in it is “dominant” and dominant seventh chords are very common.

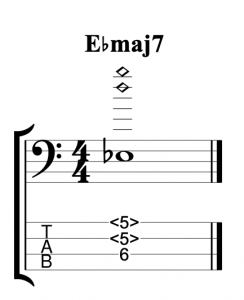

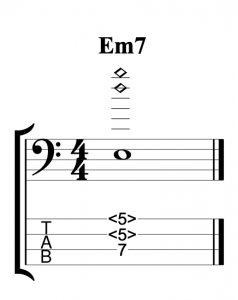

The chord symbol for a dominant seventh chord is just the number 7 (eg. G7, A7, C7 etc.) minor seventh chords are written m7 (eg. Gm7, Am7, Cm7 etc.) and major seventh chords can be written a number of ways such as with a small triangle or sometimes with an upper case M, but most commonly they are written maj7 (eg. Gmaj7, Amaj7, Cmaj7 etc.)

These three types of seventh chords are by far the most common but there are others that I’ve also listed at the end of Example 1. For example, a chord with a minor third and a major seventh is called minor with a major seventh (min/maj7).

What notes can you leave out?

When we play extended chords we usually can’t play all the notes within the chord because we only have a finite number of strings on the bass. The more chord extensions we have means the more options we have, but it also means the more decisions we have to make in terms of what notes to leave out. In the case of seventh chords the decision is simple, I’ve already mentioned that the fifth is the same for major and minor chords so the fifth doesn’t fulfill a very important function in the chord (unless we alter it as in diminished and augmented chords). So if we leave out the fifth we have three notes left, the root, third and seventh.

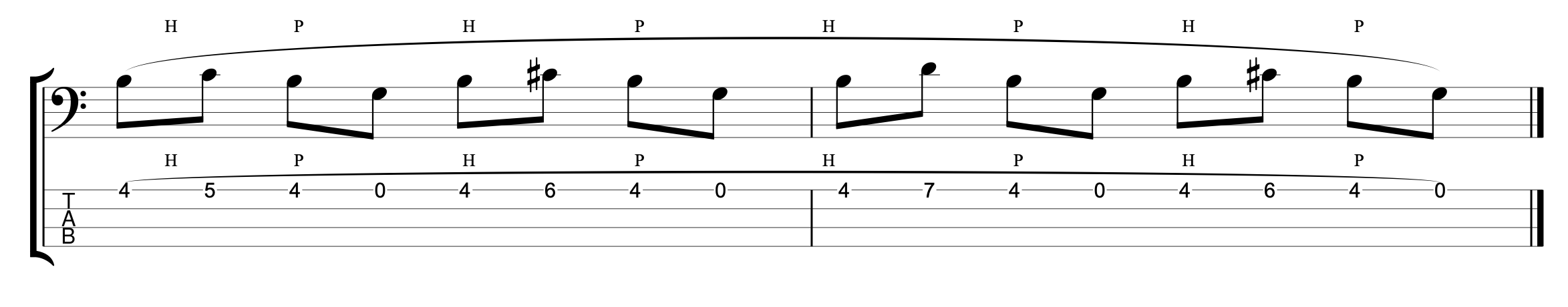

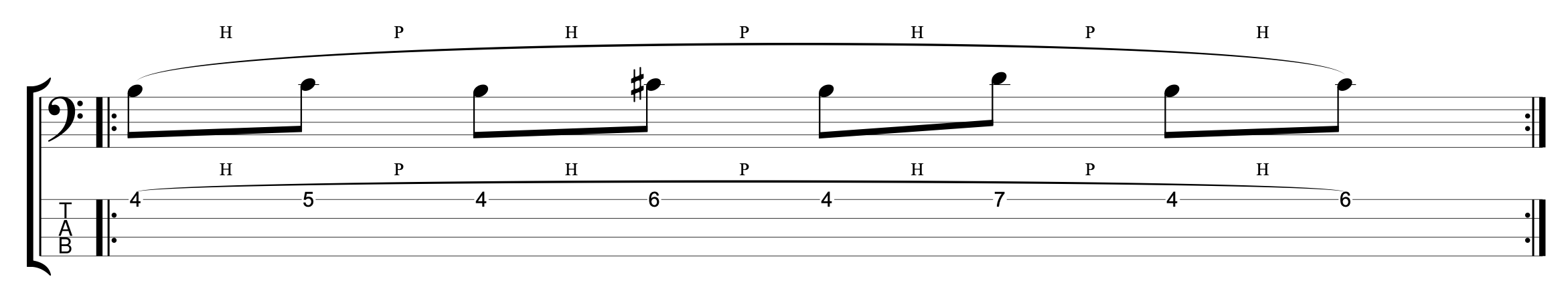

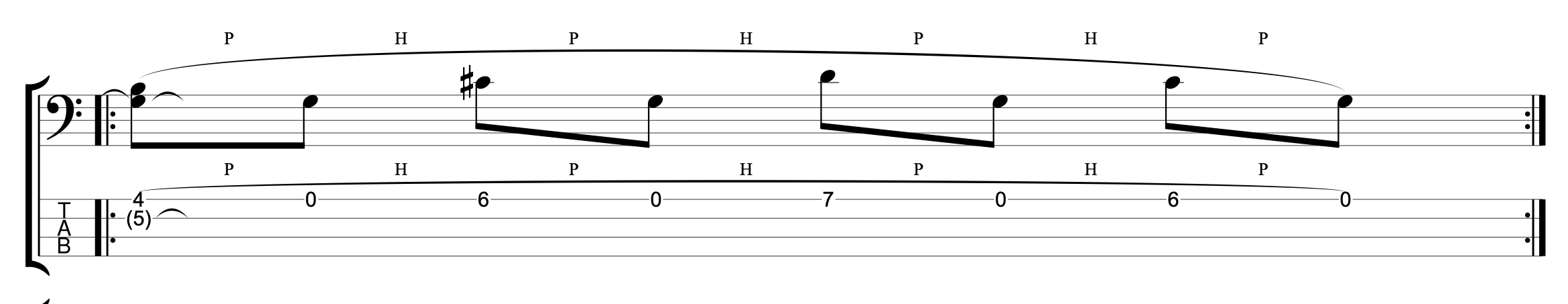

Example 1 demonstrates two different ways of voicing major seventh, dominant seventh, minor seventh and minor with a major seventh chords. The first way is to play the root on the A string, the third on the D string and the seventh on the G string. The second way is to play the root on the E string, leave out the A string and play the seventh on the D string and the third up an octave on the G string.

Altering the fifth

Altering the fifth

Just because the fifth is the same for both major and minor chords doesn’t mean we can’t alter it. You can flatten the fifth (lower by a semi-tone) to give you a diminished chord or sharpen it (raise it by a semi-tone) to give you an augmented chord. In order to play a diminished or augmented chord you need to include the fifth because the fact that it’s been altered makes it a key element in the chord. That is why I have included all four notes in the augmented and diminished examples in Example 1.

Sixths

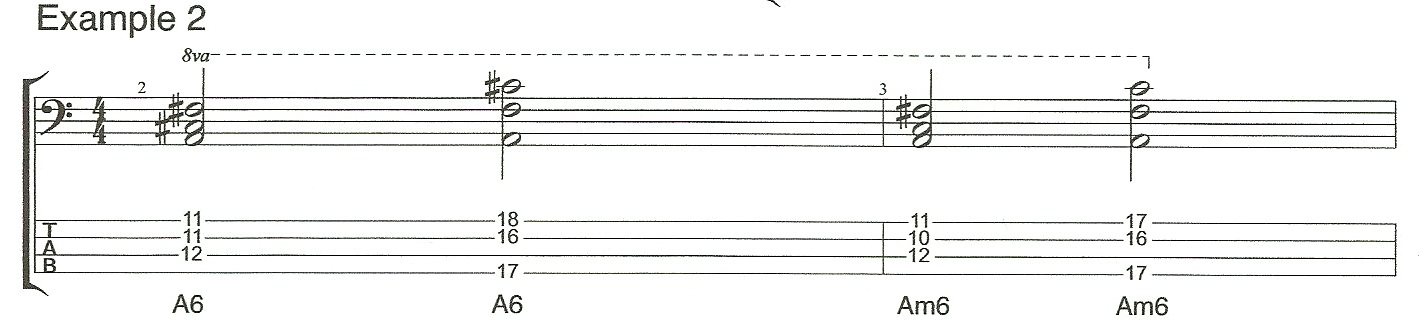

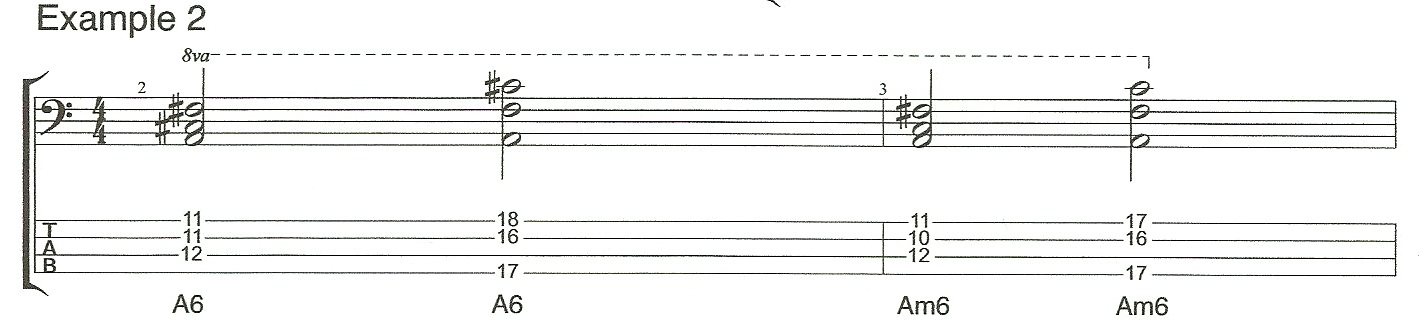

Another common chord extension that we can use instead of a seventh is a major sixth. We can add a major sixth to a major triad or a minor triad. The chord symbol for a major chord with a major sixth is just the number 6 (eg. G6, A6, C6 etc.) and the chord symbol for a minor chord with a major sixth is m6 (eg. Gm6, Am6, Cm6 etc.) Example 2 demonstrates how to play these two types of chords. Again, I’ve left out the fifth in both cases.

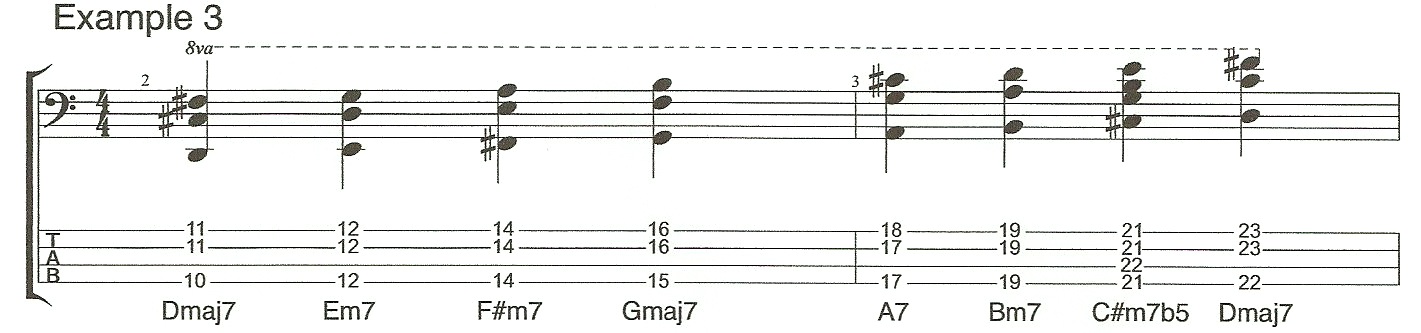

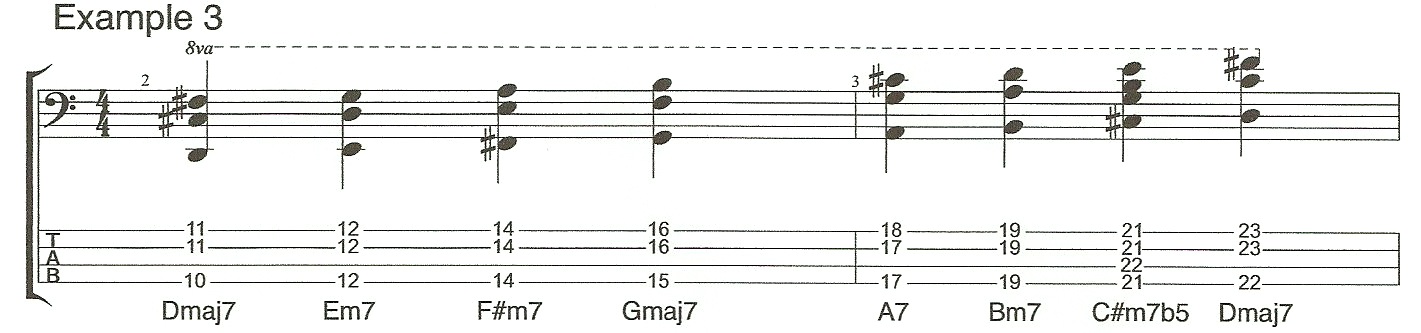

Harmonising D major in seventh chords

If we harmonise any major scale into seventh chords we get seven different chords, two major seventh chords (chords I & IV, three minor seventh chords (chords II,III & VI), one dominant seventh chord (chord V) and one half-diminished chord (a chord with a minor third, a minor seventh and a flattened fifth) (chord VII). In example 3 I’ve harmonised a D major scale into seventh chords.

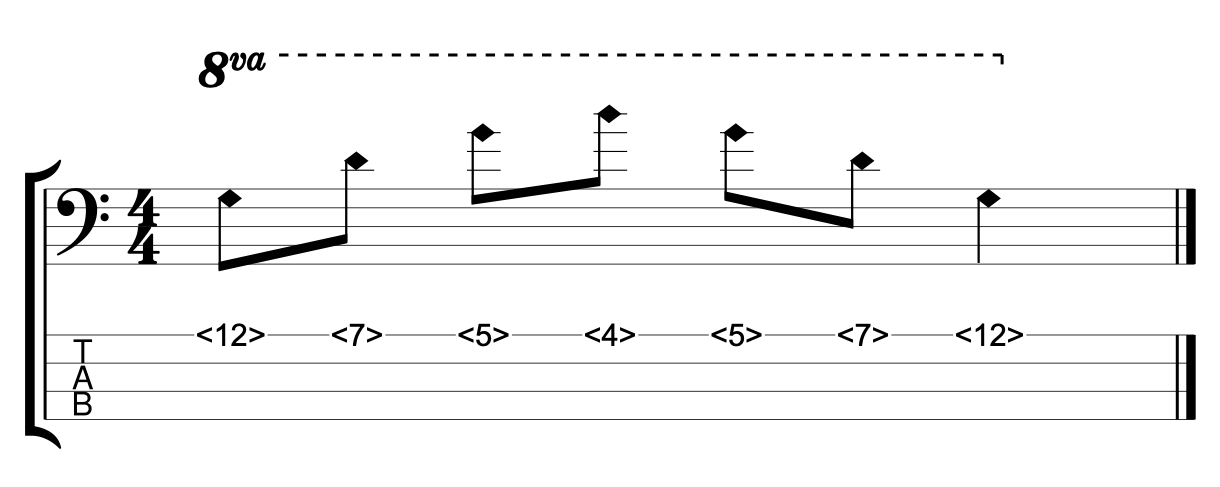

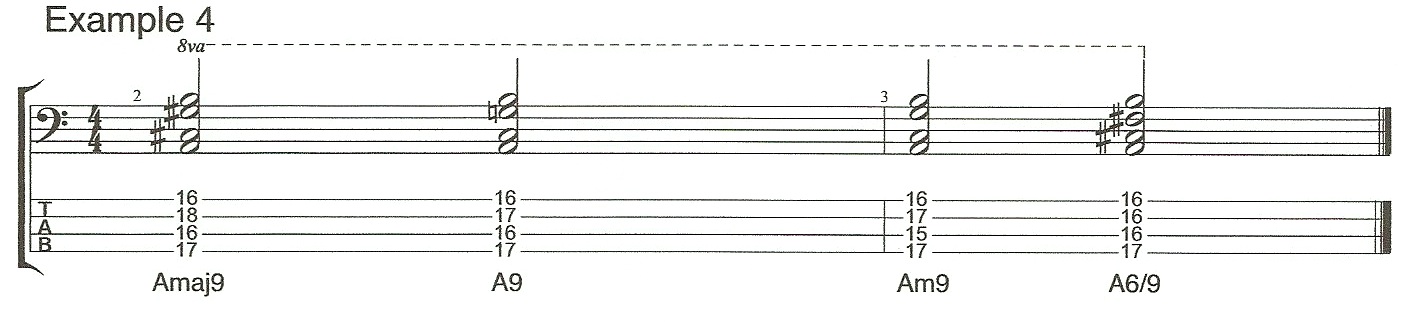

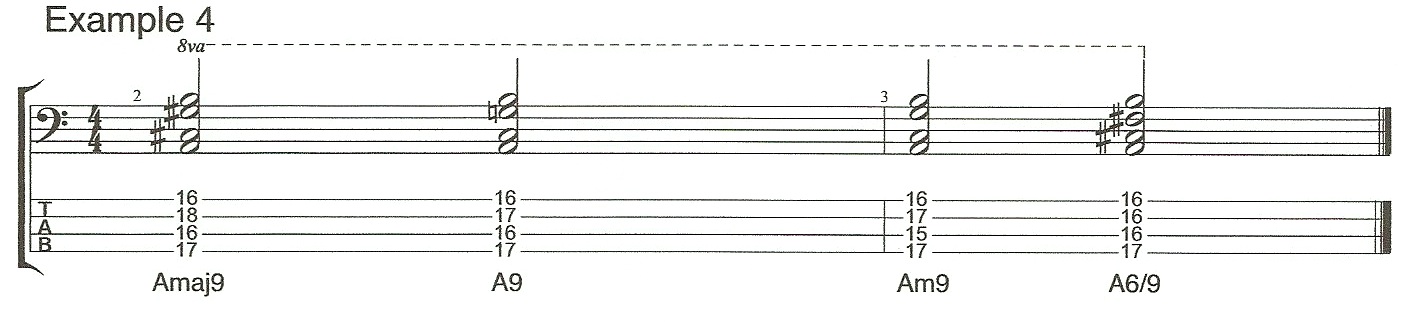

Ninths

After the seventh, the next extension we can add to a chord if we keep stacking intervals of a third is a ninth. A full ninth chord has five notes in it, root, third, fifth, seventh and ninth. Example 4, demonstrates how to play a few common ninth chords by adding a ninth to a major seventh chord, a dominant seventh chord, a minor seventh chord and even a major sixth chord. As before I’m leaving out the fifth in each chord.

More chord extensions

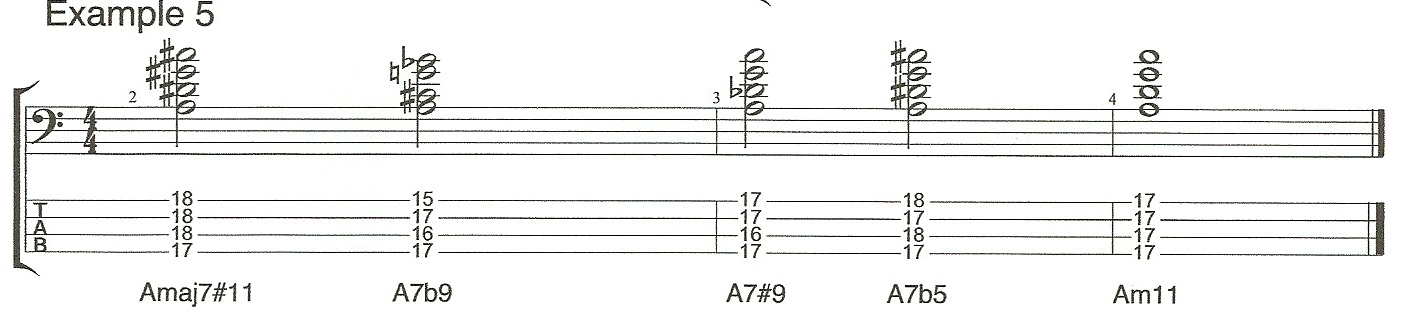

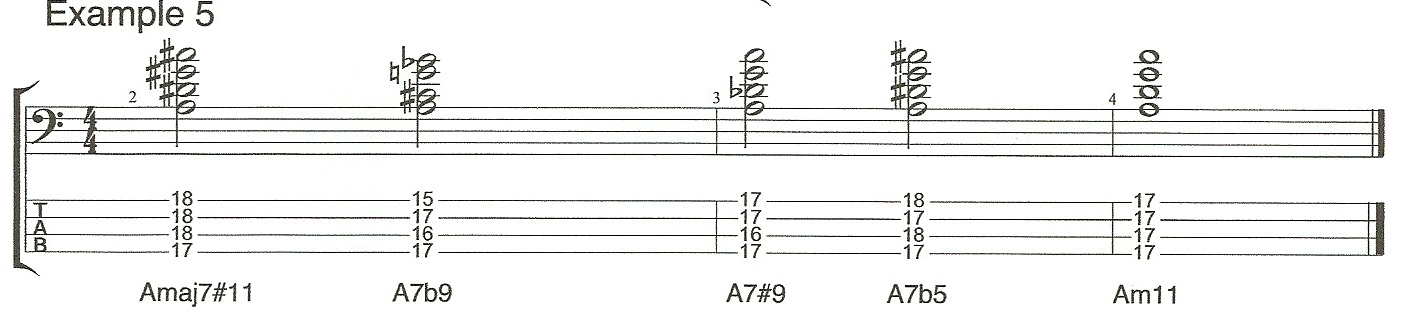

If we keep up this idea of stacking intervals of a third we end up with an eleventh and then a thirteenth. By the time you reach the thirteenth you have seven notes. Most scales have seven notes. So a seven note chord would effectively be equivalent to playing all the notes from a scale simultaneously. Which is usually a bad idea. Also, you can alter (either sharpen or flatten) the upper extensions (ninth, eleventh and thirteenth). Just like I altered the fifth earlier. This gives you a huge amount of options in terms of extending chords.

So, we have to exercise some judgement over which chord extensions we can add to which chords. And that all comes down to what we think sounds good. For example, you normally wouldn’t want to add an eleventh to a chord with a major third in it (major or dominant). Because the eleventh clashes with the third but you can add a sharpened eleventh. If you want to add an eleventh to a major chord then you would normally leave out the third. That would change the chord to what we call a “sus” chord. A sus chord is a chord that omits the third and usually replaces it with the fourth. The fourth is the same note as the eleventh. Check out my video on “intervals” if you don’t understand why the fourth and the eleventh are the same note.

Example 5 demonstrates some common chord extensions that we can play over major or minor chords on the bass.

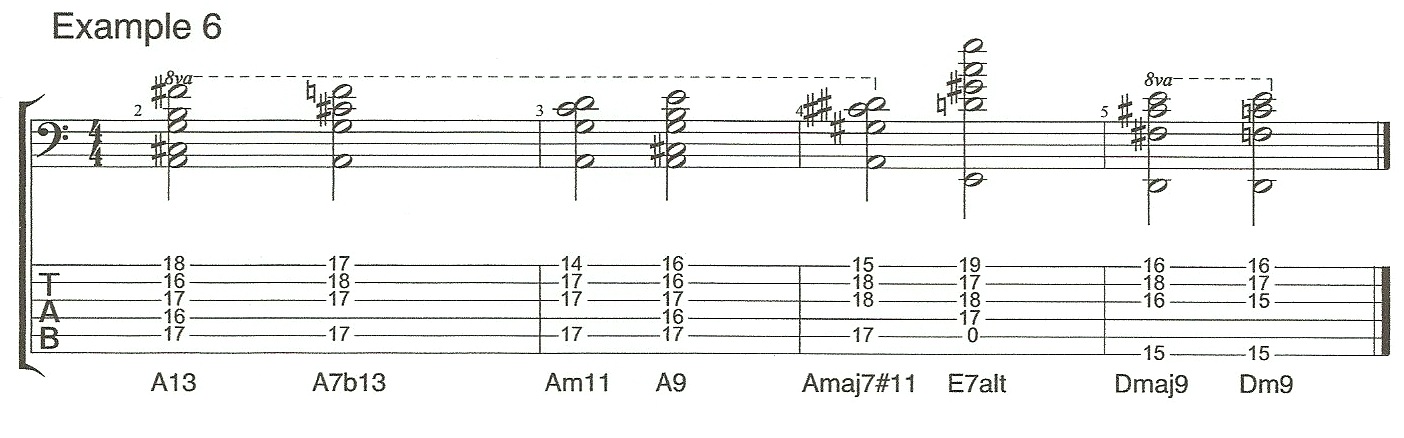

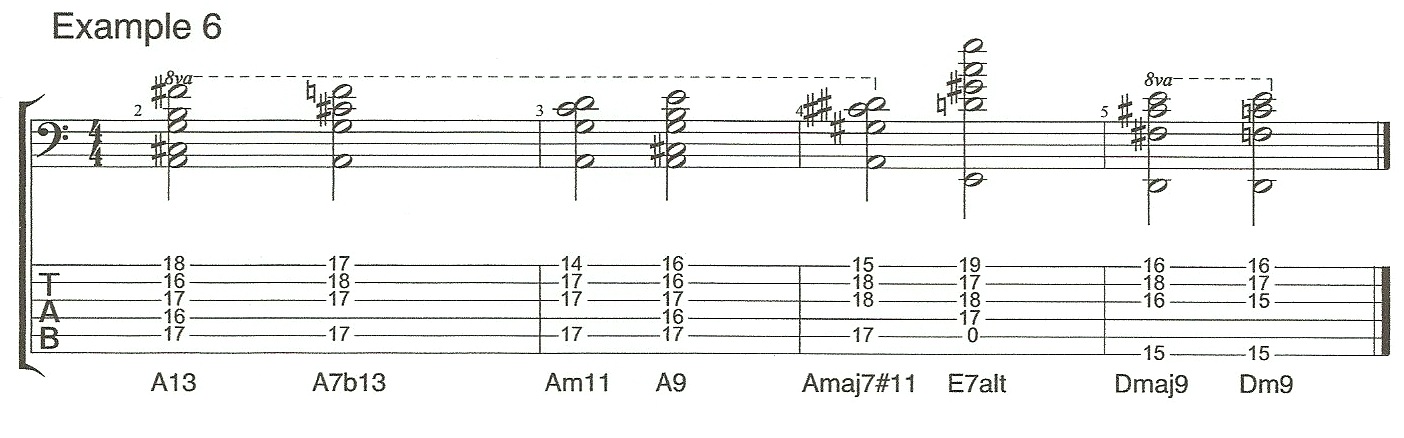

Chord extensions on 5 and 6 string basses

For Example 6 I’ve had to switch onto my six string bass to play some of these extensions. The ability to play more extended harmony is one of the main reasons I choose to play six string basses. If you don’t have a six string bass, many of these chords can be adapted onto a five string bass.